Things weren’t quite like the papers said.

From an interest in Andrew Carnegie I knew of the Meal Riots of the late 18th century. Knew a little of the aims of the Chartists, which Carnegie’s father and other radical relatives, uncles, Tom Morrison and George Lauder supported. But I knew little about the Dunfermline riots of the late 1830’s and 1840’s.

These riots mainly featured hand-loom weaver and were similar to others carried out throughout Britain at that time. The reasons for this unrest, the advent of the factory system and industrialisation coupled with a groundswell of discontent from the common working man/woman fomenting a desire to better their lot, are understandable. Reduction of Weavers’ wages, Fife Herald 1842

But I didn’t think Dunfermline’s weavers were in the forefront of militant industrial action up to and including violent rioting, arson and looting, but they were.

My enlightenment began via the pen of local author Alexander Stewart Dunfermline Riots; someone who, having lived through this period, knew first-hand what was what. He described in his reminiscences the Jekyll and Hyde character of the town thus:

“Dunfermline, which has been noted for its usually quiet and law-abiding disposition, would now and again become the scene of lawlessness, and display a riotous aspect.“…

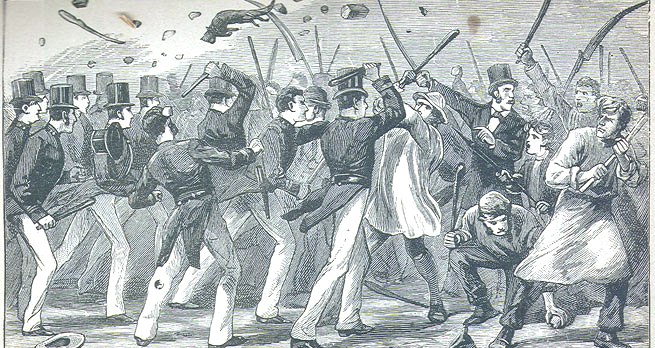

…”I remember seeing one or two other mobs on their way to wreak their vengeance on those who had incurred displeasure in connection with trades’ disputes and strikes. They’ swept along at night, and the peculiarly ominous and angry sound of voices was heard in the distance. The ringleaders nimbly climbed up the public street lamps and put them out, leaving some streets in darkness. On they came pell-mell, the crowds consisting not only of men and lads, but also of women. Some of the foremost of them had blackened faces, and carried sticks in their hands. On arriving at the doomed houses the work of destruction went furiously on, and the women sometimes vied with the men in their efforts to destroy dwellings and looms.”

Soon, my image of my old home town, with couthy cobbled lanes and corbie-gabled homes wherein gentle weavers once worked, soothed by the tolling of the abbey bells, was replaced by the reality of a harsh, hard, place with equally hard residents.

Stewart’s description of his home town persuaded me to look further into this “riotous aspect”. This I did by reading accounts of some riots before the Irish navvies arrived to build the railways.

The most comprehensive history of Dunfermline is generally believed to be “Annals of Dunfermline, A.D. 1069 – 1878″, by Ebenezer Henderson, LL.D, but they have nothing of riots for this period.

Another comprehensive history, of Dunfermline’s weavers, is a book by Daniel Thomson entitled “The Weavers’ Craft”. Surprisingly Thomson says nothing about the 1850 expulsion of the Irish which involved hundreds of weavers, but he explains that another Dunfermline riot was the result of a general strike in 1837 by weavers over wages earned and rates paid by the factory owners. As the economic effects of the strike hit home, some weavers were desperate for money and worked their hand-looms in secret, but when they were found doing this by their striking comrades, mobs formed and invaded their homes and smashed their looms.

The coal miners of the area were also involved in an acrimonious strike and were drilling in military fashion, which, according to Thomson, raised fears that they would join with the weavers and try to overturn the government.

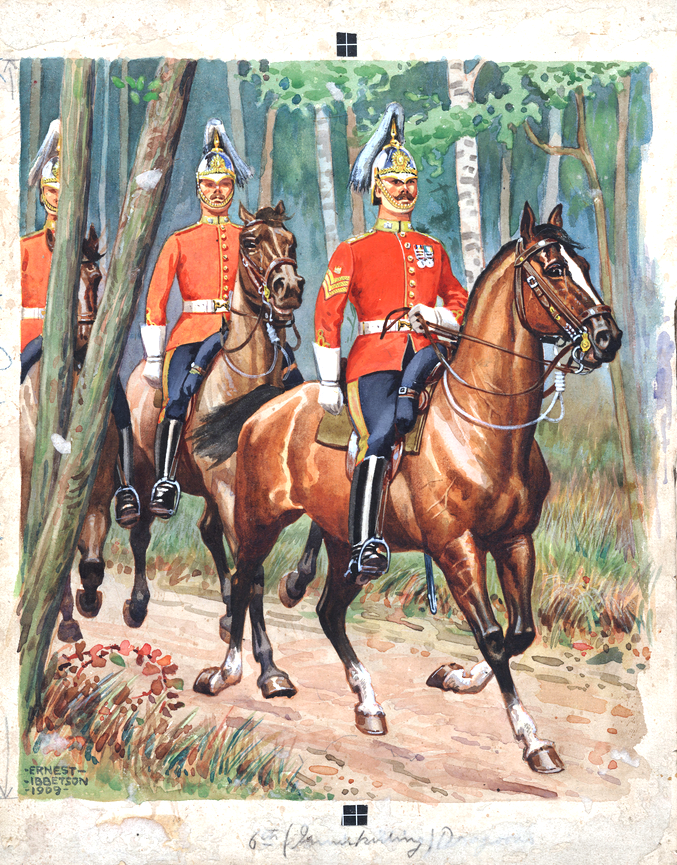

In Dunfermline at that time there was only one police officer with two assistants and a drummer, a force totally inadequate to deal with small disturbances, far less suppress an insurrection, so the Sheriff called out a troop of dragoons and foot-soldiers to restore order. CXXX The Weavers’ Craft

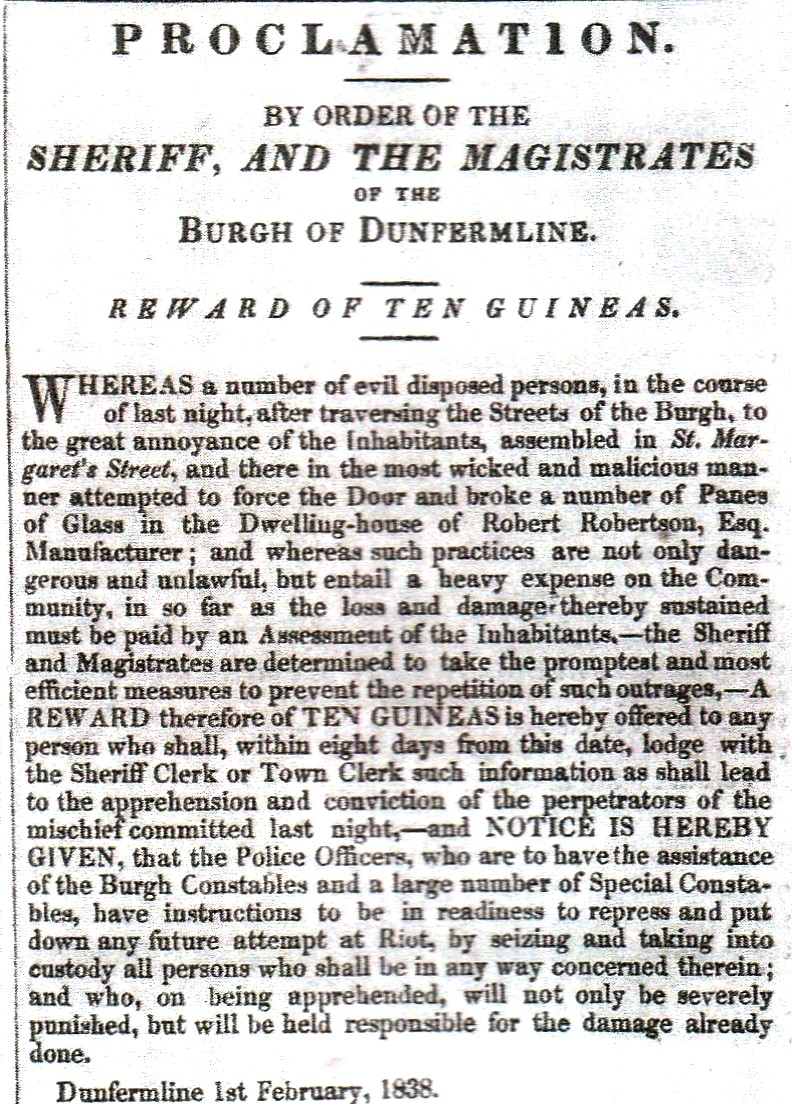

The following year, in January 1838, a riot caused the Sheriff and Magistrates to offer a reward of 10 Guineas for information leading to the apprehension of those responsible.

The above reward offer apparently didn’t act as a deterrent, as on the 25th of May that year the London Dispatch newspaper reported that it was necessary for a company of the 79th Regiment, the Cameronians, under the command of Captain Cameron to be summoned to suppress further outrages committed by the miners and weavers, which despite the dire warnings in the above notice seem to have been committed with impunity. London Dispatch 27 May 1838

It gets worse. A few years later, in August 1842, a riot erupted which involved a mob of 5,000, lasted a week and took 100 soldiers patrolling the town to put down.

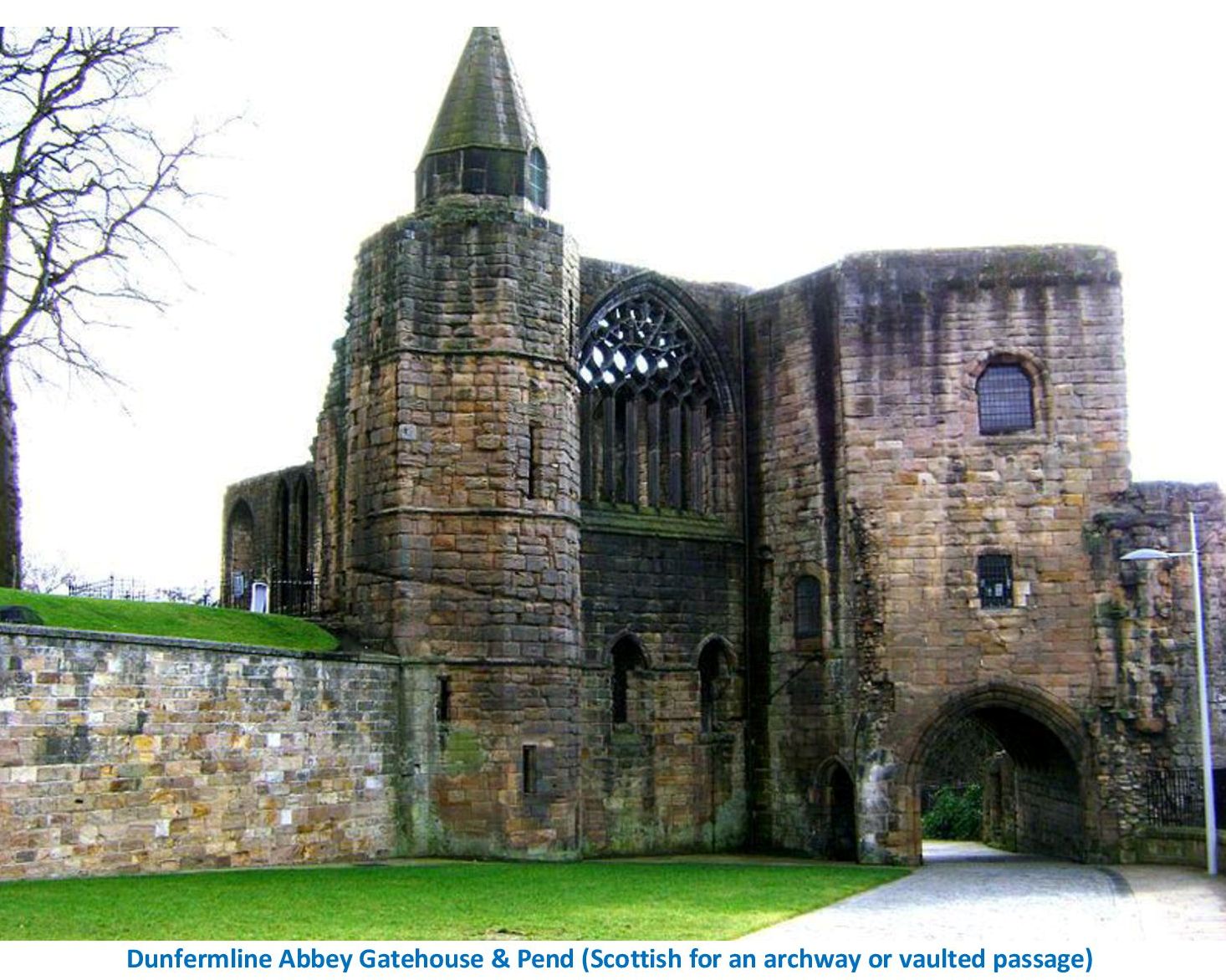

On that occasion the trouble began when all the factory owners reduced the weavers’ wages. On the Tuesday evening after this, following a meeting of weavers at the Abbey Pend (Arched gateway) area to discuss this reduction, a crowd of 5,000, led by a drummer and a standard bearer rampaged through the town. The mob stoned the Provost and police causing them to hastily retire, they then burned the looms of several factory owners, also smashing and looting a spirit shop belonging to one of the owners.

The following day several of the rioters (one of whom was arrested in a corn field beside a half-empty whisky barrel, armed with two pistols) were charged and locked up in the Town House, a wooden building that doubled as a jail.

The next day, Wednesday the 10th of August, a huge mob surrounded the Town House demanding the prisoners’ release and threatened to free them by force and fire the town house if their demands weren’t met.

The Town House by this time was guarded by a small troop of Enniskillen Dragoons who were no match for the rioters. The Sheriff Monteith who had been sent for addressed the mob from the safety of a window within and promised he would summon all the factory owners to thrash out a wages compromise if they would disperse and have a meeting of their own at the Pend. The mob dispersed and later their meeting at the Pend was addressed by Tom Morrison, leader of the Radical Party and owner of a local cobblers shop.

At the Pend meeting Morrison announced, to loud cheering, that the factory owners had caved in to the weavers’ demands. This averted the immediate danger to the Town House, but it didn’t altogether stop the trouble, as coal miners with similar grievances still posed a threat to the peace when they marched through the town armed with bludgeons and skirmished with the enlarged police force and troops who now numbered 100. Fife Herald of 11 & 18 Aug. 1842

For their part in the August 1842 riots three colliers and one weaver were charged with mobbing and rioting and received prison sentences. The President of the colliers’ association, John Henderson, later gave Crown evidence against the four rioters. National Records of Scotland

Around this time, Tom Morrison and John Henderson, the colliers’ leader, had organised and addressed public meetings at various parts of Fife and the Lothians to support striking miners. These meetings were viewed as rabble rousing by the ruling classes and at one such meeting at Torryburn on the 27th of August, the military, at the direction of the civil authorities, arrested Morrison and Henderson and locked them up in the jail at Dunfermline. They were charged by the Procurator with sedition, but were soon released after two factory owners promptly posted their bail, and their trial on this, very serious charge, never took place. CXXI The Weavers’ Craft

In 1843, the ubiquitous Tom Morrison, now a Bailie (a municipal officer and magistrate in Scotland) on the Police Commission, called for the abolition of the police force as, according to him, they were a public nuisance and an unnecessary expense! This drew an accusation from a fellow board member that he was involved in the 1842 riot and arson. Fifeshire Journal Oct 1843

The next lawless incident of note came in the summer of 1844 when troopers of the 26th (Cameronian) Regiment of Foot, stationed in the town, had a minor altercation with locals. This ‘storm in a tea-cup’ ended with the troops fixing bayonets and clearing the streets. Tom Morrison took exception to this and had words with their commander, one Captain Frederick Skinner, who Morrison called a “trifling-looking, red coated monkey”. I Predict a Riot

No humour was evident in the next riot by weavers in 1845. It was a particularly lawless and vicious one, during which the mob acted like the Ku Klux Klan, prompting the editor of the Fifeshire Journal to call for the perpetrators to face the gallows.

Again the riot arose from a weavers’ wage dispute. This riot involved a mob, summoned by the beat of a big drum, embarking on an orgy of destruction in the town and when the Provost and other civil leaders tried to dissuade them, they gave them a good kicking and carried on to wreck a warehouse belonging to factory owners Thomas and James Alexander, and the town house of Thomas Alexander..

While this was going on in the town another mob of several hundred weavers marched two miles north to Balmule House, the country home of James Alexander and set fire to the house while he was on the roof attempting to escape them. The mob then assaulted his wife with a baby in her arms, and only left when they thought the house was ablaze and “past the power of man to put it out” and their employer was doomed to perish in the blaze. Riot at Dunfermline, Fife Herald/Fifeshire Journal Aug 1845

For the crimes committed in the 1845 riot only three weavers were brought to trial at the High Court in Edinburgh. None of the accused was charged with the attempted murder of James Alexander, but all were charged with Wilful Fire-Raising, Assault and Mobbing & Rioting. A verdict of Not Proven was returned for all of the accused on the Fire-Raising charge, and only one was found guilty of the latter two charges, for which he was sentenced to be transported beyond the seas for 7 years. The other two accused were found guilty of Mobbing & Rioting only and sentenced to 12 months imprisonment each. H.M.A. v Coutts & Others.

The frequency of riots such as this one, by a well organised, secretive mob of vengeful character, was described in a follow-up article to the 1845 riot in the Fifeshire Journal, thus:

“From the details published, it is impossible to come to any other conclusion than that there in the town of Dunfermline a regular band of conspirators, organised and disciplined, with watchwords and signals, bound together under obligations of secrecy and with hearts to conceive and hands to execute any crimes however atrocious”

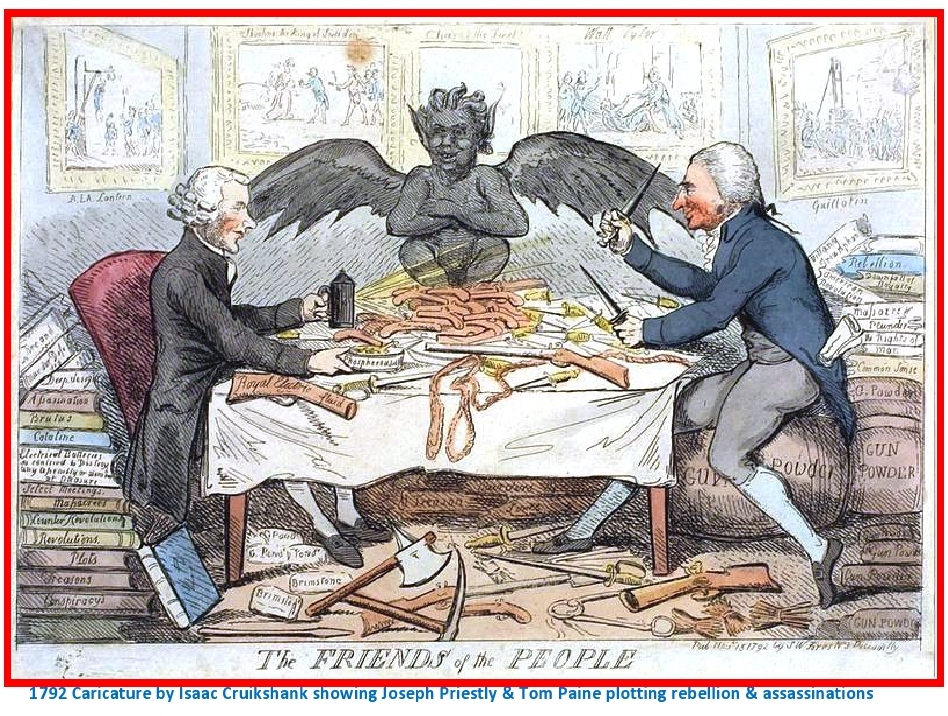

The conclusion about a secret society being behind the rioting in the above article chimes with Alexander Stewart’s belief that there was such a society, which he supposed was the “Friends of the People,” a republican body formed in Dunfermline in about 1794.

Many such societies, taking their inspiration for violent change, exemplified by the French and American revolutions, had sprung up in Scotland, and according to Stewart the Dunfermline chapter were summoned to assembly by the beat of the ‘Nethertown Weicht’, a drum made of an animal-hide head, stretched over a wooden hooped base.

As well as having a unique method of summoning members, the society had a unique motto on their banner, which alluded to their weicht, or drum, which read “May Tories’ hides become drum-heads To beat republicans to arms!”

So while much is known and published about Dunfermline’s radical movements that sought a Charter for the rights of the people, including an extension of the franchise by peaceful means, little is known, or at least written, about those who sought change by violent means.

One exception to this apparent Omertà being the American author Joseph Frazier Wall who wrote in his 1970 biography of Andrew Carnegie:

“Even in Dunfermline, among the handloom weavers, those aristocrats of labor who had always been a source of strength for the moral-force Chartists, there was an increasing impatience with gradualism. Spontaneous mob action was becoming ever more frequent in 1844 and 1845. Weavers, borrowing the disguise used by their children on Hogmanay Night, their faces blackened with soot, attacked and burned a small power loom mill that had been established in the town in 1843. The Nethertown Weicht, an ancient drum reputedly once the property of the revolutionary Friends of the People Society, was brought out of its carefully guarded hiding place, and its deep boom was the signal for the weavers to attack. One weaver carried a banner with the slogan, “May Tories’ hides become drumheads to beat republicans to arms. To Tom Morrison [Carnegie’s uncle] and Will Carnegie [his father], lying in their beds listening in the night, the distant muffled beat of the Weicht, must have sounded like a funeral drum roll to their hopes of peaceful reform.”

Leaving aside Frazier Walls’ assumption that Tom Morrison and William Carnegie only favoured peaceful reform, I had now educated myself to the fact that the image which is largely accepted of the town Andrew Carnegie left in May 1848, that dear, peaceful, historic place he waxed lyrical about, was bogus.

In fact Dunfermline was a very violent and troubled place, which was almost constantly under martial law with troops from Edinburgh and Stirling billeted there, and even as late as the August of 1848, Carnegie’s uncle, Tom Morrison, was still spreading the ideals of the French Revolution to an eager audience. C XXXI The Weavers’ Craft

To summarise; the contemporaneous press reports of the 1850 riot suggest that its cause was simply a continuation of previous jealousy and trouble between the Scotch and Irish inhabitants. But while promoting a stereotypical bad image of the latter, the reports didn’t give any of the former’s past record for organised violence as context.

This over-simplification of the issues, as being a premeditated attack by drunken Irishmen on peaceful Scots weavers ignores the weavers’ previous and lengthy violent record, encapsulated by Sheriff-substitute Charles Shirreff’s weary tone in 1850, when once again he writes to the army seeking military intervention, necessary, he explained, because: “the operatives [weavers] here are again at their old tricks after a long repose.”

So, informed by my new awareness of the harsh actuality, the facts, as opposed to the oft-repeated and rose-tinted myths, I decided to take an even closer look at the 1850 riot.

I thought perhaps I was missing something, as it seemed odd to me that the native rioters, with a proven, bad, track record, who had violently expelled the Irish inhabitants of Dunfermline, were treated with some sympathy by the press, and very lightly by way of sentence by the courts.

I’m always sceptical when reading what the press report, and as the newspaper reports of the court proceedings at the time were skeletal to say the least; I thought a good place to take a fresh look at the 1850 riot would be the legal documents regarding those convicted.

I felt there was more to this story than meets the eye, but just how much more there was, would astonish me ….

Continued in Part Three: The Charges, Prisons, Petitions & Clemency

Don’t miss it!