If Burns lived today would he have voted for Brexit?

Prior to the referendum on Scottish independence in 2014 many newspaper articles posed the question: “How would Robert Burns have voted?” So as we approach the anniversary of The Bard’s birth I thought it would be a good idea to pose the same question with regard to Brexit?

Prior to the referendum on Scottish independence in 2014 many newspaper articles posed the question: “How would Robert Burns have voted?” So as we approach the anniversary of The Bard’s birth I thought it would be a good idea to pose the same question with regard to Brexit?

Let’s look at a few facts first:

Early life as a youth in Ayrshire

Born in Ayrshire on the 25th of January 1759 Burns died in Dumfries on the 21st of July 1796, a short life, even for his times, but he packed a lot into his 37 years.

The young Burns had little schooling by today’s standards and worked from an early age on his father’s various tenancies of small farms in Ayrshire, so there is little doubt that he was of the working class and deserved his reputation as a son of the soil.

But even as a youth Burns was more than just a farm labourer and he exhibited his talent for romantic verse at the early age of 15 years when he wrote a song entitled “Handsome Nell” in honour of his first girlfriend, who had worked with him on a harvest.

From that time on Burns wrote many poems and later in life collected and wrote songs as well. My first knowledge of his poetry was his “To A Mouse” which he wrote from his observations after disturbing a field mouse while ploughing and the sentiments on this, and other poems, such as my favourite (bar one word), “Now Westlin’ Winds”, show Burns to be a man of great humanity, kindness and wisdom.

Burns the sometime radical, sometime establishment lackey, in Ayrshire 1780 – 1786

Burns lovers portray the young man as a romantic radical, because as a 21 year old on 11th November 1780 he co-founded the Tarbolton Batchelors’ Club. Ostensibly a debating society, this was but one of the many that flourished in Scotland at about this time. These clubs are credited with fuelling the Scottish Enlightenment.

The apparent radical nature of Burns seems to have disappeared or at least mellowed when the following year the 22 year old Burns was initiated as an Entered Apprentice into the Tarbolton Masonic Lodge, St. David, No 133, on the 4th July 1781, and passed & raised as a Master Mason on October 1st of the same year.

So more than halfway through his life Burns joined an all-male secret society and while these bodies are claimed by their members as being innocent fraternal meeting places, they were also undoubtedly sectarian in that their members were a self-perpetuating clique drawn from a chosen few, almost exclusively Protestant and Unionist men.

The secret society Burns was invited to join was seen by many as a means of bettering their own lot in life by the mutual help of the brethren. To those from the working classes such as Burns it was a chance to move up the social scale, to meet men from the middle and upper classes and make contacts that would help him get on in life.

The other side of Masonry is that it is also an organisation of social control from the top down as Scottish Freemasonry was always led by a laird.

In the year that Burns entered ‘The Craft’, 1781, the laird, or Grand Master Mason of Scotland was a general in the British Army, the Eton-educated Alexander Lindsay, 6th Earl of Balcarres & 23rd Earl of Crawford.

The laird at local level in Ayrshire was Sir John Whitefoord of Ballochmyle and Burns wrote to him, with due deference, in about 1781. LINK

It follows that the rank and file membership of a hierarchical structure headed by nobles have deference towards them.

There is nothing radical about being a member of such organisations.

Another apparent contradiction in Burns’ radical credentials was his strict religious observance, which saw him being repeatedly rebuked publicly for the sin of fornication. This involved him and his lover Jean Armour, who was pregnant with his children, being made to sit in the penitent’s stool at the front of the church while the minister berated them before the congregation.

I cannot reconcile the idea of Burns being a romantic, literate, principled, radical, when he allowed himself and his lover to be the subject of verbal abuse from narrow-minded clergymen as well as the scorn of his peers.

Burns the potential Negro Driver

In 1786, following the humiliation of Burns and Jean Armour he was forbidden to see her and had to go into hiding as he knew her father had writs waiting to be served on him. At about this time his farm – which he had ran since the death of his father in February 1784 – wasn’t making money either and he accepted the offer to become what he later called (in a 1787 letter to his friend Dr. Moore) a “poor Negro driver” in a sugar plantation near Port Antonio, Jamaica.

The job entailed the use of a dog and a whip on slaves in the field and Burns was fully aware of this fact and wrote about it in detail later in an epistle to his friend John Rankin.

The knowledge of what a white bookkeeper’s role on a slave plantation on the American continent is spelled out in verse, with buckskin negro slaves compared to cattle which he would herd to earn his wages of a golden guinea.

“Lord, I’se hae sporting by an’ by

For my gowd guinea,

Tho’ I should herd the buckskin kye”

For’t in Virginia. [N.B. Slaves were issued with buckskin breeches and kye is the old-Scots term for cattle]

The offer of this post came after Burns had actively sought such a position via a friend and fellow Mason (Master of Ayr Kilwinning Operative Lodge, 123), Dr Patrick Douglas of Garallan, a local doctor with investments in estates in Jamaica. The doctor also seemed to share Burns’ passion for the ladies as he was reported to be a member of the ‘Beggar’s Benison’ society.

The doctor’s brother Charles, was a resident manager living at ‘Springbank’ on the ‘Ayr Mount’ sugar plantation and he had a vacancy for an assistant overseer.

Burns booked passage to Jamaica on the Greenock sloop Nancy, which he cancelled and booked on another ship, which he also cancelled and then another ship, and while Burns quite literally missed the boat in his endeavours to become a slave driver, the principle of doing such a job was something about which he seems to have had no qualms, being more concerned with Mr. Armour’s writ, and feeling angry and forlorn about his own circumstances. LINK

Apologists for Burns portray his planned move to Jamaica as some sort of well paid bookkeeping job on a salary of £30 per annum with little input into the day-to-day running of a slave plantation, but this is nonsense, Burns was to take a dog with him to drive negro slaves like cattle and be paid very little for the task (£10 per annum).

I disagree with the benign interpretation of Burns’ views on slavery. In his poem: ON A SCOTTISH BARD, Gone to the West Indies, he muses on how he might flourish there and compares his improved circumstances in an economy flourishing through black African slave labour there as being bonnily, like a white lily thus:

Fareweel, my rhyme-composing billie!

Your native soil was right ill-willie;

But may ye flourish like a lily, Now bonniely!

Now Burns of all people knew what it meant to self-identity with the flower which he uses extensively in his works as exemplifying white and fair. E.g. The Blue-Eyed Lassie

‘Twas not her golden ringlets bright,

Her lips like roses wat wi’ dew,

Her heaving bosom, lily-white,

It was her een sae bonnie blue.

To my mind the use of a white lily flourishing in a land rich on the suffering of black slaves has connotations of Burn’s own prospects, written as it was in 1786 when he was penniless and his departure for Jamaica imminent. He certainly wasn’t sad, thinking of slaves suffering, rather bullish about his own prospects.

This much is clear from his letters and from the splendid research and publication of new evidence on this aspect of Burns’ life by Clark McGinn of the Centre for Robert Burns Studies, University of Glasgow.

McGinn is an authority on The Bard and specialist speaker at Burns Suppers who reluctantly concludes in his paper “The Planting Line”: “Much as it grieves me, these new-found letters can easily be read to show that Robert Burns sought to prosper from chattel slavery and only dropped the opportunity because a better offer came along, not because of any moral scruples over human suffering“

To view The Planting Line click on this: LINK

Burns the star in the South West

One of the things Burns did before his impending flight to Jamaica was to make a book of some of his collection of poems in the Scottish dialect and have them published. He prudently left out of this collection any controversial works that were critical of the Kirk and State, and his book, the “Kilmarnock Edition” was published and within weeks he had made a profit of £20.

£20 sterling was a lot of money, the equivalent to two years work in Jamaica, and of course it rendered the Jamaica project redundant.

On the back of this overnight success Burns found that he was a popular man in his rural area. The great and good were now happy to be associated with Burns and he left Ayrshire with the good wishes of his lodge Master, Sir John Whitefoord, who suggested that Burns should go to Edinburgh, make a Second Edition of his works, available by subscription only, and buy a farm with the proceeds.

Burns’ new-found fame meant that he was able to borrow a horse on the recommendation of James Dalrymple of Orangefield (named after William of Orange), another senior Ayrshire Mason who also gave him a letter of introduction to his wife’s brother in law, the Earl of Glencairn.

In late November 1786 Burns set out on his borrowed horse for Edinburgh to further his new-found fortune and fame.

Burns a superstar in Edinburgh

Only two days after arriving in Edinburgh, on the 30th November 1786, Burns met the Earl of Glencairn, who agreed to be his patron. LINK

Glencairn’s patronage led to introductions to many of his influential friends and one in particular, William Creech, a publisher was, arguably, the most important figure in Edinburgh literary circles.

Burns and Creech had one thing in common – leaving aside their freemasonry – in that they had both been founder members of ‘debating societies’. Burns on the 11th of November 1780 had founded his Tarbolton Batchelors’ Club and Creech, while a student at Edinburgh University, had, on the 17th of November 1764, founded The Speculative Society of Edinburgh. LINK

The two ‘debating’ societies were only 70 miles apart in geography, but worlds apart in influence, as were the respective mother lodges of these two Masons. Burns’ humble lodge in Tarbolton village was populated mostly by the rural working classes with a Lord at the head, while Creech’s lodge, Canongate Kilwinning No2, lodge was populated by all of the great and good of Edinburgh, the movers and shakers of Scottish society.

One such influential member was writer Henry Mackenzie’s whose review of the Kilmarnock edition of Burns’ poetry in the literary magazine “The Lounger” for December 1786, described him as “the heaven-taught ploughman” and likened him to a Scots Shakespeare.

So it was that after little more than a fortnight in Edinburgh, Burns was able to boast to his Ayrshire friend, fellow Mason and partron, the former Provost of Ayr, John Ballantyne, in a name-dropping exercise par-excellence, that he had arrived and he enclosed a copy of The Lounger to prove it. LINK

With such great acclaim Burns had no difficulty having Creech publish his Second, “Edinburgh Edition” which, was subscribed in full making him rich and he was soon to be made even richer when on 17th April 1787, at the house of Henry Mackenzie he signed a ‘Memorandum of Agreement’ whereby he (Burns) would receive 100 guineas from Creech in exchange for the property rights to his works.

Burns was the darling of Edinburgh high society and he revelled in it. Where in Ayrshire he had did his carousing with farm workers at the Tarbolton Bachelors’ Club (members must be a professed lover of one or more of the female sex) in a 17th century thatched cottage in a quiet village, at Edinburgh he now moved in loftier circles. Here Burns mixed mainly with young authors, businessmen, advocates, lawyers, Writers of the Signet, who made up the membership of “The Crochallan Fencibles”, a club that met in an inn at Anchor Close, just off Edinburgh’s vibrant High Street.

The Crochallan Fencibles, members were ranked on military lines with office-holders having grand titles such as Colonel, etc. and to this day still meets once a year in the Officers’ Mess at Edinburgh Castle.

Burns had several portraits painted of his handsome face and one adorned the inside cover of his Edinburgh Edition, but the painting that I believe sums up the Bard at this time is the one of him being installed as the Poet of Canongate Kilwinning Lodge, an event that did not take place at all, or at least certainly not as portrayed, but what this painting does portray is the type of people that Burns wished himself to be seen, and associated with, in Edinburgh.

These are the people he described in his second letter to John Ballantyne following his visit to a lodge with the Earl of Balcarres, The Grand Master Mason of Scotland, where he was met with great acclaim by prominent members from various lodges, to whom he was hailed: “Caledonia’s Bard”. LINK

All of the above named Masons who assisted Burns are featured in this painting which is entitled:”The Inauguration of Robert Burns as Poet Laureate of the Lodge”

Canongate Kilwinning lodge has an interactive copy HERE where one can scroll over and see the names of all the notables.

Why don’t you try to put faces and figures to all of the men listed above?

If you do you will note that other than the ploughman, Burns, there are no commoners depicted!

The good times that Burns enjoyed in Edinburgh didn’t last for long and high society grew tired of the novelty of their ploughman poet, and he with them. With Creech having copyright of his works Burns was only receiving a pittance from those who subscribed to his work, and only then when he could persuade Creech to part with it, so he returned to his roots at intervals travelling back and forth between Ayrshire/Dumfries and Edinburgh.

Burns the farmer once again, briefly

By the summer of 1787 just one year after his arrival Burns was growing weary of living in the capital and had made tentative plans to return to the west of Scotland. To this end he made a grovelling petition to his main patron, the Earl of Glencairn, “that he wished to get into the Excise” and could the noble lord use his influence to get him such a job, which, he said, would spare his aged mother, brothers and sisters from destitution. LINK

Prior to this, in May 1787 Burns had left Edinburgh for a tour of Scotland and while on tour accepted an invitation to stay for a few days at Blair Castle, the family seat of John Murray, fourth Duke of Athol. LINK

At the time of Burns’ visit (September 1787), the Duke was a member of the House of Lords as well as being Grand Master Mason of the Antient Grand Lodge of England, and he boasted the only private regiment in the British Army. The regiment was raised in Perthshire as the 77th Regiment of Foot (or Atholl Highlanders, or Murray’s Highlanders) in December 1777 and (barring one brief disbandment) still exists to this day.

While at Blair Castle a fellow guest was Robert Graham of Fintry, recently appointed as one of His Majesty’s Commissioners of the Scottish Board of Excise. It is not unlikely that this meeting had been engineered by some of Burn’s influential friends to help achieve his goal of becoming a customs officer.

Burns left Edinburgh for good (other than an occasional one day visit) on the 24th March 1788.

On returning to Dumfries Burns bought Ellisland farm, which he said he intended to work by his own hand, and he had a house built there to be a permanent home for his wife and family. The family expanded at Ellisland, but his bank balance didn’t and with the farm running at a loss Burns needed to enhance his income.

In the summer of 1788, Burns made another plea for a Mason to come to his aid, this time the man was not an old acquaintance, but a recent acquaintance, Robert Graham of Fintry, H.M. Commissioner of Excise, and it was to him in that role that Burns wrote the first letter pleading for his support in his application for employment as an exciseman, which, he stated, was needed to spare an aged parent “from the jaws of a jail”. LINK

In early August 1789 Burns learned that he had been successful in being appointed to the post of Excise Officer for the 10 parishes of Upper Nithsdale. This post involved a good deal of travelling on horseback to ale-houses in that district (Sanquhar the centre of Upper Nithsdale is 20 miles from Ellisland farm, and the nearby village of Wanlockhead is the highest village in Scotland), where he was to act as a “Gouger”.

As the name implies this was not a senior customs post, but involved a person testing the gauge or strength of ales or spirits to ensure that they had not been diluted. The job also included attending polling stations, court appearances for tax defaulters, and last but not least, catching smugglers.

Neither the timing, the location, the terrain, nor the nature of the post itself was what Burns had in mind; he wanted a permanent, stationary post local to his home and a supervisory post at that.

Burns appears to have written a second letter to Graham of Fintry on the 31st of July 1789, but whether this awful draft was used: LINK or some other is not clear as it was written when he was drunk or delirious, but what is clear from it is that John Mitchell of the revenue service is now conspiring with Burns and Graham to shoe-horn Burns into a post and forcing another exciseman out.

N.B. Late revision:

At a late stage in the writing of this blog I located a published version of the final edition of the above draft letter. So rather than replace the draft I think it is better to include both (sober & drunk) versions. It is clear from this revised version that Burns has dropped his references to books by Leadbetter ( Leadbetter, Charles: “The Royal Gauger; or, Gauging made Perfectly Easy, As it is actually practised by the Officers of his Majesty’s Revenue of Excise” &Symons, Jellinger: “The Excise Laws Abridged. Second Edition. London, 1775”) and an instrument for gauging the contents of firkins in ale gallons called a ‘Brannan’s Slide Rule’. Perhaps when he sobered up after writing this he realised that his professed enthusiasm for ‘Gauging’ knowledge and equipment might lead Graham to think that he was happy as a common gouger when in fact his eyes were set on much higher, supervisory, office in the excise profession. LINK

Burns again wrote to Graham of Fintry on the 23rd of September 1788, this time with even more urgent Masonic distress signals. In this latest letter Burns again informs Graham that he knew that Leonard Smith, a neighbour of his and the local excise officer held a post at Dumfries, which was only 5 miles from Ellisland. Smith, according to Burns, was a “wealthy son of good fortune Mr Smith” who didn’t need his generous salary as much as Burns did. So would Graham remove Smith, or other “officers who could be removed with more propriety than Mr. Smith” to make way for him at Dumfries.

To my mind this is tantamount to a plea to a Commissioner of H.M. Customs and Excise that he sack officers for no other reason than to make way for Burns: LINK

It is clear that Burns, with the aid of John Mitchell and Graham of Fintry have managed to circumvent the normal rules of excisemen – that they not be posted in their home area and have to serve a probationary period as an Expectant before being promoted to the rank of Officer of Excise – from a letter Burns sends to his old friend and Royal Arch Companion, the lawyer Robert Ainslie. LINK

Ainslie and Burns had visited the Scottish borders in 1787 and on the 19th of May at Lodge St Ebbe, Number 70, they were both admitted into the Royal Arch Chapter. So it is not surprising that Burns had felt free to boast to Ainslie that rules that had been broken by Masonic preferment to allow his advancement and he also disparaged the customs service he only paid lip-service to.

It seems to me that the oath he took as a customs officer was as nothing to that of the Royal Arch and the promised blood-curdling penalties for breaching the latter made it the more binding of the two.

Burns the exciseman

Burns seems to have been unable to get Graham to change his job position immediately, or defer his starting date, because it is seen from correspondence that he had been working as gouger on a salary of £35 per annum for a brief period before he became a fully fledged Customs Officer.

And it was in this position that on the 27th of October 1789, before a Justice of the Peace and one of His Majesty’s Excise Commissioners, Robert Burns swore before God, an Oath of Allegiance to King George III of Great Britain and Ireland & Duke and prince-elector of Brunswick-Lüneburg (“Hanover”) in the Holy Roman Empire.

The oath is as follows: “I, …………………., do swear that I do, from my Heart, Abhor,

Detest, and Abjure, as impious and heretical, that damnable Doctrine and Position, that Princes excommunicated or deprived by the Pope, or any Authority of the See of Rome, may be deposed or murdered by their Subjects, or any other whatsoever. And I do declare, that no foreign Prince, Person, Prelate, State or Potentate hath, or ought to have, any Jurisdiction, Power, Superiority, Pre-eminence or Authority.”

It is difficult to accurately track the career of Burns with the excise service as in correspondence he downplayed his position and his salary in pursuit of a better job (such as those to Graham) or as in February 1790 when he wanted Peter Hill, the Edinburgh bookseller, to purchase some books for him he pleaded poverty along the lines of : “I am a poor, rascally gauger, condemned to gallop at least 200 miles a week to inspect dirty ponds and yeasty barrels” LINK

That the career of Robert Burns in His Majesty’s Customs & Excise enjoyed success beyond his ability is self-evident and confessed by the man himself. So it is no surprise that by this nepotism he was promoted to Customs Officer at the Port of Dumfries in December 1791 at a salary of £70 per annum.

The salary of £70 per annum was mentioned in a letter Burns wrote to his friend and Royal Arch Companion, Robert Ainslie in 1791 LINK yet in the months before his death he told other friends his salary had been reduced from £50 to £30 because he was unable to work.

Burns maintained his position with the excise service until his death in 1796, though his career was almost curtailed following two incidents towards the end of 1792.

Ah! Ça ira! Ça ira! Ça ira!

On the evening of the 30th October 1792.at the Theatre Royal Dumfries ‘As You Like It’ was performed for the members of the Caledonian and the Dumfries and Galloway hunt and an audience, which included the great and good such as the Marquis of Queensberry, as well as ordinary members of the public.

When the National Anthem, ‘God Save the King’ was played at the end of play the more conservative members of the establishment stood up to join in while the more radical members of the public called for the orchestra to play ‘Ça Ira’, the anthem of the French revolutionaries, who had, a few years earlier, deposed their King, Louis XVI and declared a republic.

In the melee that followed there were conflicting reports as to which side Robert Burns, one of H. M’s. excisemen was on, or if he remained neutral. Rumour had it that he remained seated, or mouthed the words Ça Ira!

An almost identical incident is said to have taken place a few weeks later on 26 November 1792, when an actress, Louisa Fontenelle, performed several works in the theatre, including a recital of a poem written for her by Burns entitled “The Rights of Women”, which began with lines from the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen”, a civil rights statement written in 1789 during the French Revolution, and ended with the cry of the revolution: “Ah! Ca ira! The Majesty of Woman!!!”

The timing of these incidents was unfortunate for Burns because a few months later, on the 21st January 1793, while his alleged conduct re Ça Ira and his poem ‘Rights of Women’ were still being talked about they took on even greater importance and became the subject of enquiries by H.M. Excise, when the French revolutionaries executed their former King, Louis XVI by guillotine.

Then, days later on 1st of February 1793, France declared war on Britain and The Netherlands. So what had been a popular, harmless, republican phrase from a song, sung by people of a friendly nation took on a very different tone in Britain, a monarchy at war and under threat of invasion by an enemy.

At this time Scotland, like the audience in the Theatre Royal, Dumfries, was split into two camps, the Unionists who favoured the status quo and the burgh reformers or Republicans who had seen, by The American Revolution of 1776-83, that Britain could be defeated, now saw the French Revolution of 1789, which encouraged them afresh.

The prospect of Scotland being an egalitarian country like the USA and France may have been attractive to Burns, who had republican sympathies, but he had promised loyalty to the King as a condition of his employment.

The rumours of Burns’ Francophile sentiments were rife, and he wrote to his patron Graham of Fintry in December of 1792 when he learned that he was to be investigated on the instructions of His Majesty’s Commissioners of Excise by Mr. John Mitchell, a revenue collector who had been given the following remit: “to inquire into my political conduct, and blaming me as a person disaffected to Government.” LINK

Against this background, political purdah was declared by Burns as can be seen in a letter to his patron Mrs. Dunlop, in which he temporarily gave up all hope of advancement in the excise service as there were twenty on a rotation list in front of him and vowing to keep his nose clean he stated: “I have set, henceforth, a seal on my lips, as to these unlucky politics”. LINK

Royal Arch Chapter Masonic distress signals go out

On this inquiry into his political conduct Burns wrote again to his patron on the 5th of January 1793, protesting his innocence, explaining that he may have known one or two people who held radical views, but that he was innocent of the charges. He openly invoked the precepts of the Royal Arch Chapter in his professed loyalty to the Monarch of Great Britain who was the Keystone of that secret society. As to his passive role in the ‘Ça Ira’ riot he stated: “I looked upon myself as far too obscure a man to have any weight in quelling a Riot; and at the same time, as a character of higher respectability, than to yell in the howlings of a rabble.”

But despite Burns’ professed distress he nevertheless, in a draft of the same letter, took the opportunity to advise his Masonic patron and Excise Commissioner friend that there is a Mr. McFarlane, a Supervisor of Excise who is gravely ill in the Galloway District with a paralytic affliction which is unlikely to improve and that he, Burns, is just the man for his job.

This plea for another man’s, highly paid Supervisor’s job is included in the original manuscript of his letter but missing from the letters published in books of Burn’s letters, such as that by Sir Walter Scott who may have omitted it to spare his fellow Mason’s reputation.

LINK Draft from 7-page Manuscript at Burns Museum

LINK Published letter by Sir Walter Scott in “The Letters of Robert Burns” , London 1887

It is hard to overstate how serious the charges against Burns were. This was in the year when many societies favouring political reform like that in France had sprung up all over Britain. The Scots parties aped the ‘London Association of the Friends of the People’ and a purge on these Scots parties in 1792 by Lord Advocate, Robert Dundas, with the help of the infamous judge Lord Braxfield, saw their leader Thomas Muir of Huntershill sentenced to transportation to Australia for 14 years on the 31st August 1793.

So the stakes were high when on the 31st of January 1792 Burns again wrote, pleading for help from his friend and Masonic brother Graham of Fintry, who as a commissioner had inside knowledge of the charges levelled against him, and who in turn advised Burns of their nature.

Burns wasn’t slow to ask Graham to speak up on his behalf and in his pleading of innocence he resorted to openly calling on Graham’s support as an obligation to a fellow Royal Arch Companion

The Holy Royal Arch plea apparently did the trick and armed with his advance knowledge of the charges against him and supported by Graham’s letter testifying to his total and absolute loyalty to King and country Burns was cleared of the charges against him in 1793.

Burns escaped with only a caution against his future conduct and a verbal and written warning from Mr. Corbet of H.M. Customs’ tribunal stating: “that my [Burns’] business was to act, not think” and to be “silent and obedient”. This order from the excise investigation panel chairman had the effect of putting Burns on probation and in fear of his job if he took any part in anything remotely disloyal or controversial. LINK

Still not content with his present role as exciseman Burns continued to lobby Graham with written pleas to effect his further promotion to a higher rank, the rank of Supervisor at a salary of £200 per annum, but it appears that even though he wrote several grovelling poems in flowery praise of Graham he had exhausted any more favours, Masonic, Royal Arch, or otherwise, from the laird of Fintry.

Although his main benefactor, Glencairn, had died and Graham of Fintry appeared to have exhausted his aid, or perhaps his patience, Burns continued with his crusade for advancement in the excise service almost to his dying day.

The range of patrons Burns employed to help him in his excise crusade was wide and not confined to Scotland. He had petitioned Dr. John Moore of London in particularly cringe-inducing terms in his quest for a more lucrative post (“Supervisor or Surveyor General,etc”) in H.M. Customs service in 1793. LINK

In another letter, just a fortnight before he died, Burns was still seeking a better deal with the excise service and to this end he wrote from Brow to his old friend and companion from the Crochallan Fencibles, lawyer Alexander Cunningham, urging him to lobby HM Excise on his behalf, a plea boosted by a promise that he would name one of his children after him. The ailing Burns was at the open-air, iron-rich, fresh water spring at Brow on the banks of the Solway Firth bathing in an attempt to cure his failing health. LINK

Silenced by threats from H.M. Excise, the reconstituted Burns becomes a willing warrior?

At the time of the Excise Service’s investigation into Burns’ alleged radical political sympathies in December 1792/early 1793 Burns wrote to his patron, Mrs Frances Dunlop on the 2nd of January 1793 stating “I have set henceforth a seal on my lips, as to these unlucky politics”.

Then when he was given written warning by his excise employers that his: “business was to act, not think” and to be “silent and obedient” he certainly towed the party line.

The extent to which Burns was curtailed in any, even remote or implied criticism of the status quo was demonstrated by his decision to reject a job offer (through an intermediary) from James Perry the owner of The Morning Chronicle, a radical London newspaper. Perry had previously – in 1791 – offered to move Burns and his family to London to work full time for that paper, now in 1793 the climate of suspicion as to Burns’ politics was such that he made it clear that his job was at risk if it was known that they published his Ode: “Scots Wha Hae”, at his behest so he asked the paper to state they had come to it by accident and unbeknown to the author. LINK

As if to demonstrate to his employers that he was a reconstituted man in 1795, in the aftermath of the ‘Ça Ira’ affair Burns emphasised his new-found enmity to Scotland’s oldest ally, France, and his loyalty to His Majesty The King, when once more he became a founder member of an organisation, this time a military one, the Royal Dumfries Volunteers.

Following on from France’s declaration of war there was, at large in Britain, a fear of invasion from France, which prompted Burns and 62 others to form the Dumfries Volunteers on the 31st of January 1795. To this end they petitioned the King a few days later as follows:

“We . . . hereby declare our sincere attachment to the person and Government of His Majesty King George the Third ; our respect for the happy Constitution of Great Britain. … As we are of opinion that the only way we can obtain a speedy and honourable peace is by the Government vigorously carrying on the present war, humbly submit the following proposals to His Majesty for the purpose of forming ourselves into a Volunteer Corps, in order to support the internal peace and good order of the town, as well as to give energy to the measures of the Government.”

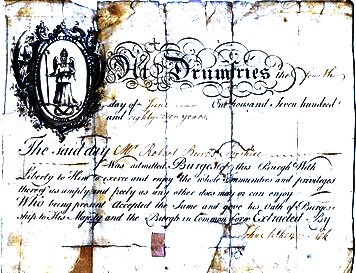

Burns at this time was a resident in the Royal Burgh of Dumfries, having moved there in 1791 when he renounced the lease on his farm at Ellisland, but he was no ordinary resident, having been sworn in as a Burgess on the 4th of June 1787. Burns was sworn in, free-gratis, as a Burgess allowing his children to have free schooling and other benefits and this was one of six such honours bestowed on him by different Scottish Royal Burghs.

The position of a Burgess, which is much like that of a freeman of a borough in England, entitled Burns to certain privileges, but it also placed upon him certain responsibilities, such as loyalty to the King, the Provost and the Royal Burgh and this obligation was pledged under a loyal oath as set out in the photo below.

Burns the Burgess attended the inaugural meeting of the volunteers at Dumfries on the 28th of March,1795, took the Oath of Allegiance and signed-up to obey the Rules &, Regulations of this corps of H. M. armed forces.

The Dumfries Volunteers, like any regular army corps, had weapons (muskets pistols and swords), uniforms, held regular drills etc. and were governed by a committee of all the officers and eight men, one of whom was Burns.

In October 1795, Burns, as a member of the Corps Committee, helped draft a Loyal Address to the King. This came following an attack on George III when he was on his way to the House of Lords. The address stated:

“To the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, the humble address of the Royal Dumfries Volunteers.

“Most Gracious Sovereign, We, your Majesty’s most dutiful and loyal subjects, composing the Corps of the Royal Dumfries Volunteers, penetrated by the recent and signal interposition of Divine Providence in the preservation of your most sacred person from the atrocious attempt of a set of lawless ruffians, humbly hope that your Majesty will graciously receive our unfeigned congratulations.

“Permitted by you, Sire, to embody ourselves for the preservation of social tranquility, we are filled with indignation at every attempt made to shake the venerable, and we trust lasting fabric of British Liberty.

“We have directed our Major Commandant to sign this address in the name of the Corps assembled at Dumfries, 5th November 1795.”

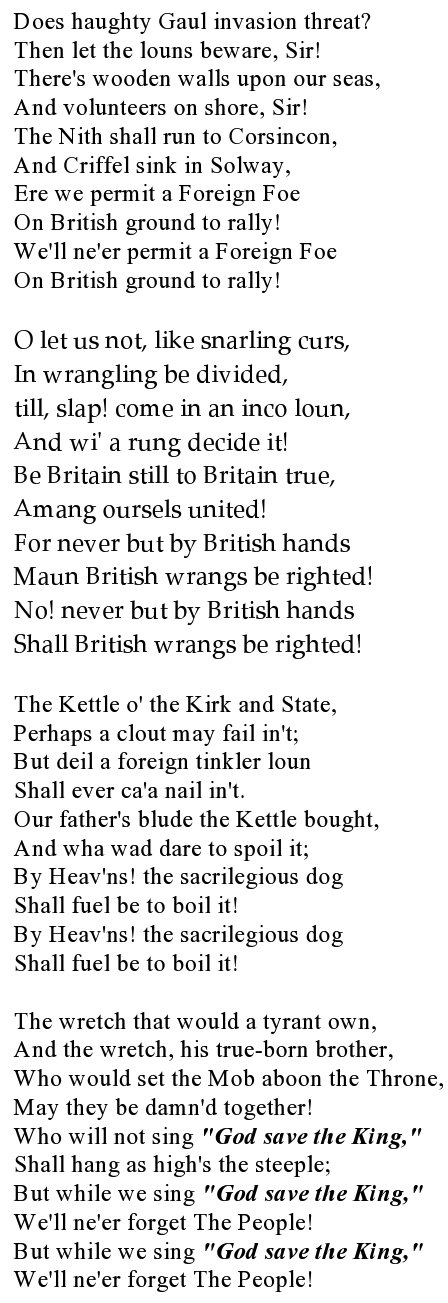

As Burns was the poet in Masonic lodges, then so was he in the volunteers. In that role he wrote a poem about the threat of French invasion and how that would be repelled by British subjects of His Majesty The King. This poem was set to music and became very popular. It was entitled: “Does Haughty Gaul Invasion Threat?” (also known as ‘The Dumfries Volunteers’) and went like this:

It seems that with such jingoistic demonstrations of Britishness Burns’ rehabilitation was accepted by his employers in H.M. Excise service as complete and in late December 1795 he was granted his wish to be appointed as a Supervisor (the poor paralytic Mr. McFarlane’s post?). LINK

The career of Private Burns, Rbt. in the volunteers was a relatively short one. From his enlistment till he was buried with full military honours was just short of 16 months, but in that period he seems to have been a good soldier and a well turned-out one, as he had his uniforms tailor-made, something that caused him grief to his dying day as he was pursued by the local tailor’s solicitor for his unpaid bill.

It is a matter of some surprise to me that his comrades in the regiment did not settle the disputed tailor’s bill, as it would have been a matter of common knowledge that he was being pursued for payment, but it can be seen from two letters that Burns wrote on the same day, one to his cousin James Burnes in Montrose for a loan of £10 to pay “A rascal of a Haberdasher to whom I owe a considerable bill” and one to George Thomson of Edinburgh “to implore you for five pounds. A cruel scoundrel of a Haberdasher to whom I owe an account” that he had to go abroad for the loans to pay the tailor. LINK

Just less than a fortnight after these letters were written though, his comrades certainly did him proud, that is at his funeral, when the 20-strong firing party of volunteers marched in file before the coffin with arms reversed. The rest of the regiment followed behind the coffin. At the grave at St. Michael’s Churchyard cemetery the 20-strong firing party of volunteers discharged their muskets in a volley over the grave

Two other regiments had attended the funeral procession, The Angusshire Fencibles and The Cinque Ports Cavalry, whose brass band played the ‘Death March’ during the solemn procession.

It was not unusual at this time for there to be regiments from outwith the area stationed at Dumfries, or in any British town, because while the Dumfries Volunteers were recruited from, and limited to, a 5-mile radius of the town, regular soldiers were posted outside of their home area so that they weren’t well known to, or over-familiar with, the local population.

It is worth noting that the Cinque Ports Cavalry who would have polished their brass buttons, their horses’ brasses, and their sabres for the funeral of their fellow soldier, Private Robert Burns, would, within 13 months, have the same sabres bloodied as they slashed them down from their horses onto the heads of innocent people in a cornfield outside of Tranent, in what has come to be known as The Tranent Massacre. LINK

One local woman wrote: “The number of wounded is not yet ascertained, but I am just now informed that fifteen dead corpses were this morning found in the corn-fields; and it is not known how many more may be found when the corn is cut, as the Cinque-ports Cavalry patrolled through the fields and high roads, to the distance of a mile or two miles round Tranent, and fired upon with pistols, or cut with their swords, all and sundry that they met with. Several decent people were killed at that distance, who were going about their lawful business, and totally unconcerned with what was going on in the town. I am informed that this was unprovoked on the part of the people, for they assembled peaceably by public intimation from the Lord-Lieutenant and his Deputies”

One wonders what the volunteer soldier Burns’ reaction to this event – triggered by the opposition to conscription into the army to fight the French – would have been, had he lived 14 months more to see it?

Would he have exploded in poems and letters of protest in support of his fellow Scots, or would he have sided with His Majesty the King, as he did when the rabble, as he called them, called for Ça Ira at the Theatre Royal Dumfries?

SUMMARY

I posed the question: “If Burns was alive today would he have voted for Brexit?” and after giving the matter some thought I have to say that I can’t answer my own question.

He probably would have said that he voted against it, and then let it be known that he voted for it, or vice-versa, depending on the company he was in, but considering his willingness to work as a slave driver in his early years and his later anti-French stance he would not have been out of place in the company of Nigel Farage if he were alive today.

Any reading of the letters of Robert Burns will see that he was a bit of a snob and a hypocrite, basking in the company of the titled, rich and famous and praising them with sickening sycophancy (read his ‘epistles’ in praise of Graham of Fintry et. al.) while writing scathingly about their like to his common, fellow-man. Hinting that he loathed subservience to royalty and then tripping over himself to pledge allegiance to His Majesty The King on many occasions.

Burns’ true feelings are hard to gauge in his written works and if one takes arguably his most famous poem/song Green Grow The Rashes O’. In the popular version of this work he praises the lasses (young women) in the most reverential way, but in a different version of the same work published in a bawdy collection of songs/verse entitled The Merry Muses of Caledonia he reduces the lassies into mere orifices, the young with tight round vaginas, as if made with a drill or wimble and the older ladies having cunts that were gaping wounds; large gashes.

I could go on to give other examples of Burns’ two-facedness, but I recognise that he, like all of us to some extent, compromise our principles in order to feed our families.

To summarise my opinion of Burns in this respect I would use the Scottish dialect beloved of The Bard and say “he’d mair faces than the toun clock”

That said, if I admire a songwriter, playwright or poet it doesn’t really matter to me what they are like as a person – within limits. So, while not being a big fan of poetry, I don’t have a problem with The Bard’s snobbery or hypocrisy. No, to me his major fault was his cynical use of Masonic influence to get one over on his fellow man.

Scotland has the biggest per capita Masonic membership in the world and it is also one of its biggest problems. In over half a century of working in the engineering industry where freemasonry is rife I have known many good Masons, but I have seen many Leonard Smiths striving for promotion only to be overtook by talentless individuals whose only gift was a handshake.

Burns was an extraordinarily talented man and he may have made his way as an artist without the help of all his Masonic contacts, but without them he may not have. But the same can’t be said about his expertise in matters of excise.

And what of the other artists of his age with talents equal to Burns’ who did not have the letters of introduction to the great and famous Masons, who would not so much open doors for their brethren, but would push others aside and kick the door down for them?

I say this as someone who succeeded in business despite not being a Mason, but who watched others with no talent soar and corrupt meritocracy as they did so. I’ve seen too many good men pushed aside by the Burns’ of this world.

I realise that my view probably won’t be popular as I have noticed how anyone who criticises Burns’ conduct, as opposed to Burns’ works, is attacked from all sides. Liz Lochhead was a case in point when she attacked Burns’ misogyny. Be that as it may, there is a Feedback function on this website which allows questions or criticism to be sent, at which time I will peruse and perhaps reply.