1816 – 2016

To mark the bi-centenary of the sale of the so-called ‘Elgin Marbles’ to parliament in 1816, I decided to review my 2004 entry and update it with new information and arguments that I feel were not adequately covered in my 2004, ‘Elgin Cheated at Marbles’ blog.

At the moment it looks as if there will be three new blogs, this one, which is the subject I feel most passionately about, one on the Memorandums, and lastly a general Critique of the Elgin Marbles affair.

☠ = Hyperlinks

Elgin’s Grave Robbery: His Greatest Sin.

A grandchild, a crumbling pier and a press photographer get me started

In my first, 2004, blog entitled: “Elgin Cheated at Marbles”, which dealt with Elgin’s looting of the Parthenon and other sites in Greece, I should have explained what caused me to take an interest in the subject. It happened like this:

2001 Recently retired, my wife and I took our 2-year old granddaughter Millie to a beach near our home in Dunfermline. The beach is at Limekilns, a small village on the north shore of the River Forth.

The village’s name is taken from the large lime kilns on the shore, which once fired limestone, quarried a short distance away at Charlestown (named after the 5th Earl of Elgin). The kiln firing process made the stone suitable as an ingredient of lime-mortar or as a fertiliser.

Making sand-castles with Millie on the shore, a journalist asked me if we minded if he used us as perspective to a photo he was taking of the pier. I agreed and asked the nature of his story, which he said was about the local laird seeking public money to help him repair his crumbling pier. [ Update 01/06/2021 Though the Earl of Elgin promised to fix his pier years ago he didn’t keep his promise and has instead leased it to a community charitable trust, who are raising funds to repair it (including funding from the National Lottery), then hand it back to the Elgin’s when it is in good condition. LINK ]

I didn’t have a problem with the local laird (Andrew Bruce, 11th Earl of Elgin), but had recently exchanged words with his eldest son and heir, who had tried to stop me from walking on a road that runs through Broomhall estate, something I had been doing for 45 years.

Anyway, the reporter’s story got under my skin, because as I saw it, the laird, the 11th Earl of Elgin, was a rich and privileged man whose family had, in times gone by, made fortunes from the lime quarry, kilns and piers on their land. But now that they had problems they were seeking help from the public purse, while at the same time they were restricting long-established public access rights through their estate.

Help! My flue lining’s gone and there’s smoke belching out everywhere.

I checked the facts of the matter out with the lawyer for the local authority, Fife Council, and then, being an awkward bastard by nature, I cheekily wrote to him asking him to consider granting me some public money.

I reasoned that as his council were helping distressed genteel folk he might consider helping me with the costs of repairing the cracked flue (chimney lining) of my house.

My tongue-in-cheek appeal was aimed at highlighting the absurd, grovelling attitude of many in my country, when dealing with the aristocracy.

This started an exchange of letters to the press that ended up with me being assured by local politicians that the 11th Earl would not have his way with the pier, but the public wouldn’t have their way on the road.

So neither I, nor the 11th Earl, got any public assistance to mend the masonry on our properties.

There was a difference between us though, in that I never professed to be an expert on masonry, while he did (both kinds), and he regularly told the world, via the press, that his ancestor had only taken the Parthenon masonry because the Greek people couldn’t look after it for themselves, and we couldn’t return it Athens for the same reason.

To me, this reeked of arrogance and double standards.

Taken by the writing of a man whose name I couldn’t pronounce.

My brush with Elgin’s descendant in the pier episode prompted me to widen my vague knowledge on the subject of what is commonly known as the Elgin Marbles.

I had managed to stumble through my schooling without having been taught much, and certainly nothing about the so called ‘Elgin Marbles’, so I went online to educate myself, and of the various articles I found on this controversial subject was taken by one in particular; a booklet written by a professor by the name of Epaminondas Vranopoulos.

Chapter 10 of the professor’s booklet dealt with Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin’s grave robbery, as described in an anonymous 1815 Memorandum.

Chapter 10 of the professor’s booklet dealt with Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin’s grave robbery, as described in an anonymous 1815 Memorandum.

Prof. Vranopoulos’s ire was raised by the fact that Elgin used this anonymous document as justification for his actions as well as ‘talking-up’ the selling price for his Greek plunder, at a time when our cash-strapped former ambassador was touting them to the British government.

The professor seemed most annoyed by Elgin’s grave robbing, noting that “Elgin’s team dug up and looted the graves of Euripides and Aspasia” and other sacrilegious acts.

The grave robbing aspects of Elgin’s Greek tragedy were news to me, but I agreed with Prof. Vranopoulos, that morally, this was a far greater outrage than the denuding of the Parthenon.

So when I finished my research I decided to complain to the police force that they should investigate the possibility that sacrilegious plunder was housed at Broomhall, the ancestral home of the earls of Elgin.

Call the cops! Tomb Raiders have been at work & I know where the loot’s stashed!

In Section 6 of my ‘Elgin Cheated at Marbles’ blog I detail my 2004, and 2009, written complaints to Fife Constabulary and the London, Metropolitan Police (Met).

Leaving aside the Met for the moment, the basis of my complaint to the Chief Constable of Fife was that I had proof that grave robbery on an industrial scale had been carried out by the 7th Earl of Elgin.

To disturb a corpse is a very serious matter in Scotland. It is classed as the crime of ‘Violation of Sepulchre’; has a long history dating back to the early 18th century and can attract long prison sentences, up to life or transportation ‘beyond the seas’ for 7 years, and such a sentence was passed in 1823, on a near neighbour of the 7th Earl, Thomas Stevenson, alias Hodge, by Lord Pitmilly.

However I couldn’t accuse the present, 11th Earl of Elgin, of being linked to this crime, as it was committed by his long deceased ancestor in a far away land.

But I could, and did, make a formal complaint that Broomhall harboured the proceeds of past grave robberies in Greece.

Accompanying my first police complaint was a CD – the forerunner of my ‘Elgin Cheated at Marbles’ blog – containing a copy of a catalogue compiled by M. Ennio Quirino Visconti, which detailed the plunder that Elgin offered for sale to the 1816 Westminster parliamentary committee.

The catalogue listed: “Some hundreds of large and small earthenware Urns or Vases, discovered in digging in the ancient Sepulchres round Athens”.

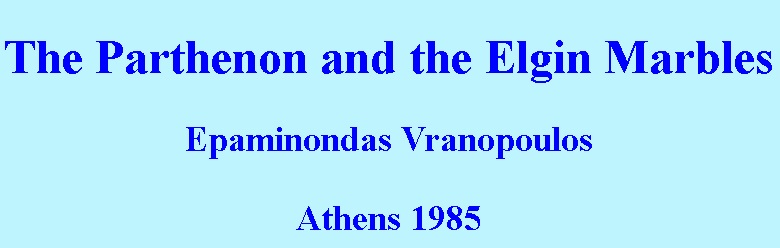

The Catalogue then itemised a dozen unknown “Cippi or Sepulchral pillars” followed by a list of sepulchral pillars, columns, epitaphs, tombstones and steles for: “Two brothers, Diotrephes and Demophon”, “Thalia”, “Theodotus”, “Socrates”, “Menestratus”, “An Athenian”, “Anaxicrates”, “Hieroclea”, “Callis”, “Callimachus”, “Plutarchus”, “Euphrosynus”, “Musonia”, “Briseis”, “Hippocrates and Baucis”, “Biotins”, “Thysta”, “Thrason”, “Asclepiodorus”, “Aristides”, “Botrichus”, “Epitaph in twelve elegiac verses, in honour of those Athenians who were killed at the Siege of Potidrea, in the year 432 B.C.”, “Aristocles” and “Aphrodisias of Salamis”.

My CD also contained the “Memorandum on the Subject of the Earl of Elgin’s Pursuits in Greece”, which detailed one particular grave robbery in the presence of the Earl and his wife; the opening of a tumulus believed to belong to Aspasia (more on this later).

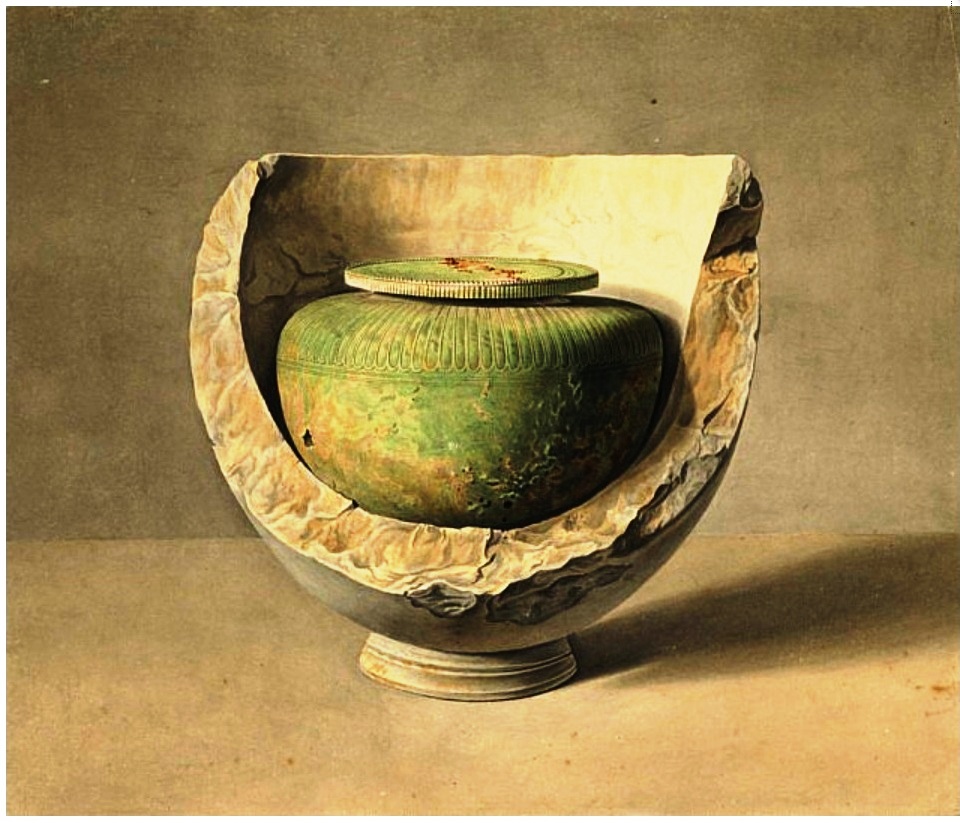

My complaint to the police was based on the 7th Earl’s admissions of grave robbery to parliament in 1816, and photographs showing the present, 11th Earl, posing at Broomhall with some of his ancestor’s plunder adorning the walls of his home.

I thought that such arrogance and insensitivity was disgusting and made this clear in my complaints to the police.

Though the police didn’t share my views in 2004, I again made a similar complaint in 2009 with new evidence that part of the looting of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing in 1860, by James the 8th Earl of Elgin was also at Broomhall.

Sadly the police didn’t see my 2009 complaint as evidence of a possible crime either and the responses from the Chief Constables on both occasions were perfunctory ones, the last one from Norma Graham, Chief Constable dated 7 December 2009, reiterated the terms of the response by Peter Wilson, Chief Constable in 2004 which stated: ‘a report was forwarded to the Area Procurator Fiscal, which included your letter along with the associated documentation you provided. In response the Area Procurator Fiscal advised ‘that no criminal act can be proved and there are therefore no grounds to investigate the matter further’.

To my mind Ancient Grave Robbery is a heinous crime despite what the police think.

Despite my rebuffs by Fife Constabulary in 2004 and 2009 I was never shaken in my conviction that grave robbery no matter when, or in what country it took place, is a crime against humanity and harbouring the proceeds of such sacrilegious plunder is the crime in Scots law of reset, which is without time bar.

To me the heartless nature of these crimes is exemplified by the inscription on one particular tombstone that Elgin looted (below) which is now on display in the British Museum:

After many pleasant sports with my companions I, who sprang from earth, am earth once more. I am Aristokles son of Menon, A citizen of the Peiraieus.

The man who would dig up and carry off such a poignant memorial must have a heart of ice.

Museums which boast of such items have no shame.

And anyone who would adorn the walls of their home with such memorials, whether they are of friend or foe, famous figures, or common folk like the lad from Piraeus, is beyond my comprehension.

Would we approve of such looting today?

Of course not!

Out of the mouths of babes comes wisdom

2015 When it came to updating my website to mark the bicentenary of the purchase of Elgin’s plunder I wondered if a young person would share my revulsion on this subject. Children’s simplistic views on complex issues are often refreshingly accurate, coming as they do from minds uncluttered by society’s slanted version of things. So I decided to ask one.

I told Rosie, Millie’s 10-year old sister the bare facts of the story of how the crumbling pier at Limekilns had prompted my interest in the Parthenon marbles, and how this in turn revealed to me the grave robbery of hundreds of burial sites around Athens.

Rosie’s shocked reaction restored my faith in my own judgement (which I had begun to doubt) – she was appalled.

As a pupil of Saint Margaret’s Primary School, Dunfermline, Rosie knew that many Scots kings and queens were buried in Dunfermline Abbey, just yards from her father’s shop.

Dunfermline Abbey was once Scotland’s Royal Sepulchre.

So I asked Rosie to imagine a scenario similar to Elgin’s 19th century plunder being carried out today in her home town.

Rosie’s reaction was one of horror. To let strangers dig up our Saint Margaret, her school’s patron saint? No way!

When I told Rosie that most people in Scotland want us to return the so-called Elgin Marbles to the Greek people, she agreed; saying that we should just: “give them back their marbles.”

Let’s make a movie.

I asked Rosie if she would let me film her having her say on those things she had remarked on at some of the relevant locations. She agreed, but anything Rosie does, her wee sister Maisie does too, so off the three of us went with my iPad, to film a short documentary for this blog.

Rosie and Maisie are experts with their iPads, propping them against a wall or chair, they film themselves doing gymnastics, singing, dancing, acting, etc. They then playback and refine their act before putting on a show.

Having watched them do this often I thought it would be a simple matter for me, a man who had successfully ran his own engineering business for 25 years, to make a simple 3 minute iPad video. Wrong!

My efforts at filming were hopeless.

In stark contrast to my pathetic efforts, Rosie and Maisie were anything but amateur, so I thought it only fair to start afresh with a professional filmmaker, so as to do them, and this emotive subject, justice.

Here is the result with a Scots accent:![]()

Here with Greek subtitles courtesy of Vaso Papadaki:![]()

I think my two wee stars did a wonderful job.

To me they did more in three minutes to illustrate the wrongs of the industrial scale grave robbery by Elgin than anyone has done in the last 200 years.

I might just be a wee bit biased with this judgement.

Elgin’s grave robbery was never discussed in 1816 or since…Why?

It’s little wonder that the 1816 parliamentary committee drew a veil of silence over Elgin’s ill-gotten loot from grave-robbery. Because, while the MPs were able to portray a vestige of legitimacy to the Parthenon denuding, by accepting Elgin’s flimsy “preservation of the arts” alibi, they could have found absolutely no justification for his mass grave robbery.

Nor could Elgin offer any. He couldn’t tell the committee that if he didn’t dig up the graves and take their contents the barbarous Turks would have. These graves had survived all manner of foreign invasion for two millennia and more intact. As Byron wrote: “But most the modern Pict’s ignoble boast, To rive what Goth, and Turk, and Time hath spared”

No, these acts were indefensible then, and now.

What my junior film crew were also able to graphically illustrate in their visit to the graveyard at Limekilns, was the fact that Elgin knew of the needs of his neighbours in Limekilns and of his own family, for land to bury their dead, and he willingly provided it.

The inscription on the monument below, which featured in the video, records the land was gifted: “as a burial place for them and their posterity”.

So respect for the dead, and those future generations who come after us (the posterity) was something Elgin understood at home. But, by contrast, in a foreign land under the yoke of oppression he used the privilege of his role as ambassador to uproot the sacred remains of hundreds, for financial gain. Hypocrisy and greed personified.

In 1812 the people of Limekilns erected a 15 foot high, obelisk-topped monument, to honour and give thanks to their laird for his gift of additional land for their graveyard.

By the same token the people of Athens should erect a 1,000 feet high Pentelic marble pylon, a colonnade of condemnation for the desecration that Great Britain’s ambassador wreaked.

A bairn wi a biscuit erse would ken that!

When something was patently obvious to my late mother-in-law, she would use her Fife vernacular to exclaim: “a bairn wi a biscuit erse would ken that”

For viewers who are not from these parts the saying implies that even a young child, one whose bottom is no larger than a biscuit, would be aware of something patently obvious. It is akin to the Irish saying “even the dogs in the street know it”.

That is the way I feel about the wrongness of disrespecting the dead and their living survivors by digging up graves and removing any valuable contents. While I was doing my filming at Limekilns graveyard something happened that reinforced my certainty about this.

Leaving the footpath we walked across the grass to be near the monument. Maisie became quite distressed when she realised that underneath the grass we walked on lay dead people. I tried to reassure her (“we won’t hurt them”; “the people have been dead a long time”; “they’re only bones”; “just dust”, etc.) to no avail as she was instinctively uncomfortable at the thought of walking over dead people.

Rosie and I eventually eased her concerns, but it occurred to me that the disquiet felt intuitively by a four-year old child was absent in Britain’s 19th century Imperial Ambassador and his staff.

Elgin had Visconti list some of the funereal containers, but what about the contents?

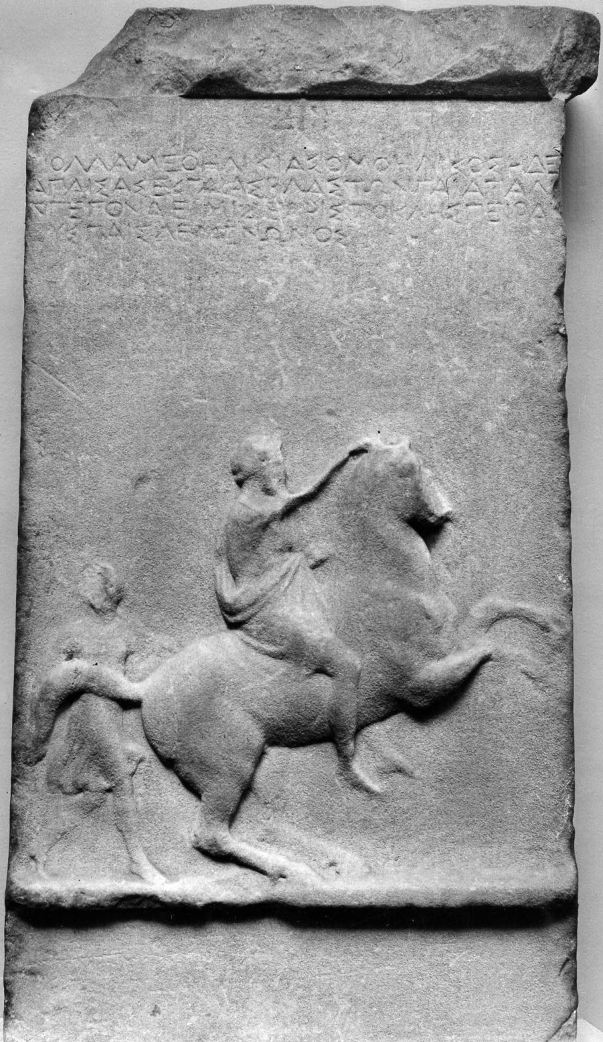

Below is a copy of an oil painting by Elgin’s resident artist at Athens, Giovanni Battista Lusieri, which is displayed in the National Gallery of Scotland. The subject is the ‘Aspasia’ Double Urn, which the Elgin Memorandum tells us was: “a large marble vase, five feet in circumference, inclosing one of bronze thirteen inches in diameter, of beautiful sculpture“.This double urn was excavated from a grave tumulus on the road leading from Port Piraeus to the Salaminian ferry and Eleusis.

We know from Visconti’s catalogue that Elgin sold parliament many of these funereal treasure-chests, so to speak.

But what of their non-human contents? Apart from three musical instruments, two flutes and a lyre of cedar wood, “found during the excavations among the Tombs in the neighbourhood of Athens” Visconti recorded no other internal contents. That is, the valuable loot from the hundreds of graves robbed.

And there would have been many valuable items buried in urns and vases with the dead. It is a matter of fact that in ancient Greece this was the custom.

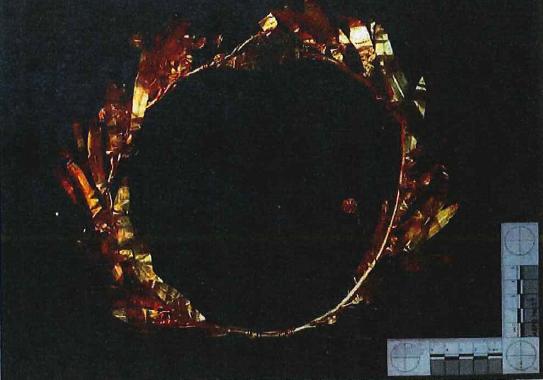

One example of this custom can be found in Elgin’s Memorandum, which describes the contents of the double urn pictured above thus: “in which was a deposit of burnt bones, and a lachrymatory of alabaster, of exquisite form; and on the bones lay a wreath of myrtle in gold, having besides leaves, both buds and flowers.”

No mention of this gold wreath was made in Visconti’s Catalogue, and I understood that it had been kept by Elgin.

In 2014 I think I’ve found Elgin’s ‘Aspasia’ gold wreath.

As explained above I had provided the police with details of the ‘Aspasia’ tumulus excavation which unearthed the gold wreath of myrtle, as evidence of Elgin’s graveyard looting with details of the loot. Loot, I reasoned the police should be searching for at Broomhall.

I didn’t expect police cars, with sirens blaring and lights flashing, to screech to a halt at Broomhall, with armed officers leaping out and smashing open the large oak doors with battering-rams, before racing inside to ransack the ancestral home of the Earls of Elgin in their search for sacrilegious plunder.

But I did want them to carefully consider what I believe to be an important issue in a world where attitudes to sacrilegious plunder are changing. Today museums are returning sacred burial artefacts to their countries of origin and I explained this in detail as a reason why I wanted them to take the principles behind my complaint seriously.

After all, the police would take it seriously if today someone reported that an ex-Black Watch squaddie, suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder – with drugs and drink issues brought on by the horrors he had seen in Iraq – was trying to sell a Sumarian gold chalice he’d looted from the National Museum of Iraq. And if this poor sod was living in a run-down flat on a sink estate then the above ‘raid’ scenario would be a reality.

To me Elgin’s crime is a crime is a crime…regardless of the passage of time.

Needless to say the police didn’t share my view and I was left disappointed; fobbed off with police platitudes.

But I was only disappointed for a short while and it was always my intention to try again after a while to force the establishment to justify the holding of sacrilegious loot in museums and homes. Make them justify the unjustifiable.

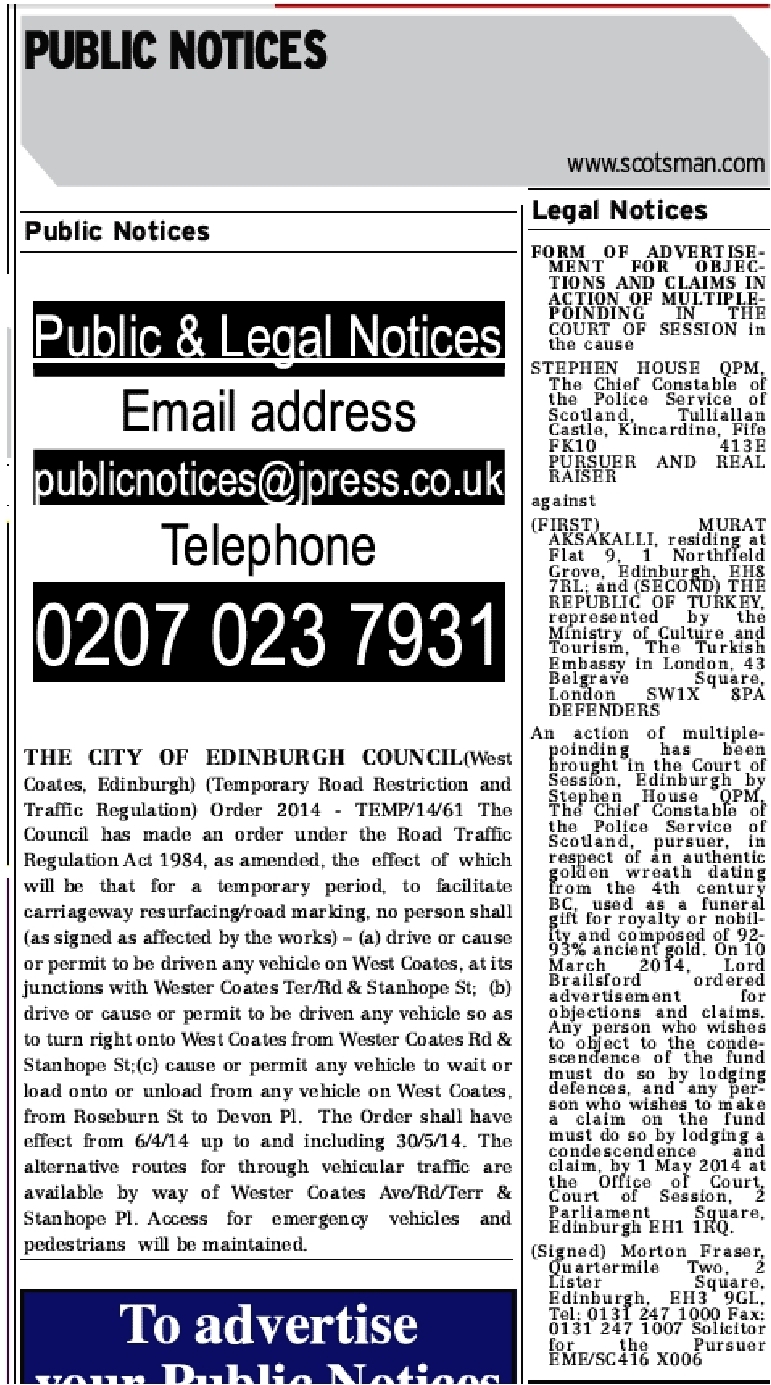

So I was very interested when I saw this notice in The Scotsman newspaper:

To paraphrase from Elgin’s Memorandum: “May it not be from the tomb of Aspasia”

Though intrigued by this advert under Legal Notices, I wasn’t sure if I had an interest in the “authentic golden wreath dating from the 4th century BC” (Aspasia died about 400 BC) or not, as there was no detailed description of the wreath.

I did know that the Elgin estate regularly sold off very valuable and unique items looted by the 7th Earl, but not sold to parliament at the time of the Parthenon Marbles sale. This is a matter of record.

And the artefacts not sold to parliament by Elgin in 1816 are not insignificant remnants, as evidenced by John Paul Getty’s intense excitement when he heard that the current laird might part with the early 4th century BC steles of Myttion, Theogenis, Nikodemos and Nikomache.

So perhaps the wreath described in The Scotsman Legal Notices might be the ‘Aspasia’ one that may have been sold by the Elgins and had now surfaced on the open market in Edinburgh, legitimately or otherwise.

However if the advertised gold wreath was not of myrtle leaves with buds and flowers then I wouldn’t have an interest in it, but if it was, I might, because it could be the one that Elgin brought home. And if that was the case, then, on principle, I wanted to claim it so that it could be returned to the site where it was taken from, namely the road leading from Port Piraeus to the Salaminian ferry and Eleusis.

To save wasting the court’s time if the wreath was of oak, olive, or any other leaf, I wrote to the judge whose order had appeared in the Scotsman and asked what type the leaf was. He declined to answer that specific question, but advised me that if I had an interest I should make a claim through the court.

I also wrote to the police who gave the same reply and wouldn’t let me see or photograph the gold wreath or even see their photographs of it.

So I followed the judge’s advice and filed a claim with the Court of Session Edinburgh and became a party to the multiplepoinding on the basis that the gold wreath might be the ‘Aspasia’ one. It certainly fitted the Memorandum description.

The arrogant, narcissistic and authoritarian Sir Stephen House as……er….impartial honest broker?

The other parties to the quaint Scots civil law suit that is known as multiplepoinding were: Stephen House, the Chief Constable of Police Scotland, who had no claim to the gold wreath, but acted as the Pursuer and holder, and two other claimants, a Turkish restaurateur and The Tourism and Culture Ministry of the Republic of Turkey.

Stephen House’s predecessor had actually initiated the action in 2013 because he was unable to determine who to give the confiscated gold wreath back to, after it was decided by the Lord Advocate that no criminal charges were to be brought against the person who owned it when it was seized. At that time two parties claimed it – the Turkish restaurateur and the Turkish Government– until I entered the fray, and then there were three.

Newspaper articles suggested the gold wreath had been confiscated by the police in Edinburgh from the Turkish restaurateur who claimed it was a family heirloom.

The Tourism and Culture Ministry of the Republic of Turkey claimed the gold wreath originated in Turkey and any historical item such as the wreath, found in Turkey, belonged, by law to the state.

Once my claim was accepted and I became part of the civil court case I was, after several rebuffs by the police, eventually able to see, by appointment, not the wreath, but a photograph of it.

Viewed by me, at a viewing table at Fettes Police HQ, with police officers behind me at either side to prevent me from taking any photographs of the photographs, what I saw seemed to be just as described in Elgin’s Memorandum: a wreath of gold in myrtle consisting of leaves (50 in No) with buds and flowers.

The grainy image below is a copy of a police photograph of the wreath taken from the report of the Turkish government.

The antipathy towards me shown by the police was puzzling as Sir Stephen House was supposed to have no axe to grind in the ownership issue of the wreath. He simply held it until the court decided who had the best claim to it; then he was obliged to hand it over to that person.

Perhaps the police’s hostility was down to the fact that unlike the other two claimants I had also objected to the condescendence of Stephen House. That is, his description of the wreath as being from the 4th Century BC and his reliance on the Turkish Government in establishing this date. All of which gave a decidedly Turkish flavour to what I guessed might be a Greek dish.

Or maybe he simply didn’t like me?

The headline above? Oh! That was how Stephen House was described by the MP Convener of the Public Petitions Committee of the Scottish Parliament. I think he was being kind to him.

Threatened by Scotland’s top cop: withdraw or else it’ll cost you dear.

Shortly after my frosty reception at Fettes Police HQ, lawyers acting for Stephen House, the Chief Constable of Police Scotland, in whose own name (as per 51.2.-(1) Court of Session Rules) the case was being brought, wrote me a threatening letter on his behalf telling me that I must withdraw or it would cost me money, and it didn’t matter if the wreath was in fact from Greece, because he had a Turkish expert report which said it was from Turkey.

The expert evidence of the wreath being a 400 BC one from Turkey that Stephen House referred to however, came from a dual 2010/2013 report prepared by the Turkish Government, who later became a party to the multiplepoinding (they would say that wouldn’t they?). So his bombast didn’t impress me much, nor did his ‘expert’ report and I told him so. I didn’t at this stage rule out the possibility that I would withdraw if I saw convincing evidence that the gold wreath did in fact come from Turkey.

From the court papers which I now had access to, it transpired that only days after the wreath was seized the police had allowed a Turkish state employee, an assistant professor from Selcuk University, to examine at least a photograph of the wreath (he may have examined the wreath itself I don’t know).

With only his limited visual examination to go on, he dated it from between 300-350 BC in the early preamble of his report before concluding it “dates to 350BC” and stating that the wreath was from the Carian region and that it was possible to associate it with the empty tomb of the Hecatomnus dynasty in Milas, Turkey (even though it was not known if that, recently discovered empty tomb, had ever housed a gold wreath).

I found it astonishing that anyone would be given access to police evidence (access that I was repeatedly refused) and even more astonishing that on a visual inspection of photographs, or even the wreath itself, a determination as to the date and place of origin of the wreath could be made. But that is what Assistant Professor Doksanalti did in his 10-page report soon afterwards.

Some time later, in 2013, following diplomatic exchanges by way of a rogatory letter* between the Turkish State Prosecutor, the Scottish government and Lord Advocate, the police gave the Turkish government the wreath to take to Turkey for testing.

*Though this critical letter was referred to in the correspondence within the bundles the Scottish Courts Service could not find it when I requested it later. ☠

While subjecting the wreath to five days of testing in Turkey the government staff said they found small traces of soil in the end of the gold tubular section. Soil not noticed by the Scottish police (would you believe it?), that exactly matched soil from the area of the Milas Hecatomnus tomb. Furthermore they insisted that a wreath of this type could only be found in the Western Anatolian area and nowhere else.

The resultant, 2013, report concluded that the wreath dated from between the years “BC 360-340“, the dates stradling the exact date (350 BC) the same Turkish Assistant Professor had said it was from after only seeing a photograph of it three years earlier in Edinburgh. This is hardly surprising as the compiler of the 2013 report was the now promoted Professor Doksanalti who had compiled the 2010 one.

So according to the Turkish Government the date and the place of origin of the Edinburgh wreath were confirmed as matching exactly that of an empty tomb that they just happened to have handy, and then they joined the multiplepoinding.

I wasn’t 100% sure if my claim for a crock of Greek gold was accurate, but I was 100% sure that the Turkish government’s reports were a crock of shit, so I remained convinced that my claim was potentially valid, and, if nothing else it might expose to the limelight the question of the legitimacy of owning funereal relics, the proceeds of looting.

Obvious bias in favour of the Turkish government suggests a political fix.

I pressed on with my claim and managed to survive two attacks by the Pursuer in court hearings at the Court of Session in Edinburgh before Lady Scott and Lord Bannatyne; both judges giving me a fair hearing.

Then, on the 20th March, 2915, I had the misfortune to appear before retired law lord Philip to argue my view that he should reject the political stitch up which had attributed a fanciful, Turkish, date and place of origin, to the wreath.

Before I could speak one word in support of my plea, this bully of a judge stated in an intemperate outburst that he knew what I was in his court for and it was to re-run the Elgin Marbles affair and he wasn’t going to allow it!

I was astonished that a retired high court judge even knew of my existence, let alone knew of my interest in this subject, and had the power to read my mind despite the fact that he had no prior knowledge of the nature of my submissions.

I protested that this was not what the hearing was about. I rightly told him the hearing was to determine if the police’s description of the wreath was correct, and if my objections to that description were valid, and insisted on reading, in full, my objection.

I then read in full my submission (38 A-4 pages at hyperlink below) on my right to file objections to the Pursuer’s false description of the wreath, coming as it did from the police’s acceptance of, and bias towards, a spurious Turkish report.

I also asked the judge to consider a public interest claim by me that because of his bias towards Turkey and against me Stephen House, the Chief Constable of Police Scotland, be found to have committed the crime of malfeasance in public office.

No surprises however when the judge, – who claimed he knew my mind better than I did – after a brief adjournment, rejected my objection to the preconceived notion of Turkish origin and date for the wreath. He also rejected my plea that an independent Scottish authority such as the Treasure Trove’s Scottish counterpart, ‘The Office of Queen’s and Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer’ (QLTR), determine the wreath’s date and place of origin.

The judge also declined to rule on the question of Stephen House’s malfeasance in public office.

The judge then awarded the Chief Constable the expenses for the hearing in court.

So that is what one is up against if one tackles the establishment on the proceeds of historical grave robbery. Especially if same might come from the house of a belted Earl, who incidentally, happened to be an ex-Grand Master Mason of Scotland.

I was bitterly disappointed that Lord Philip had failed to see the merit of my argument that the age and place of origin of the gold wreath should be determined in Scotland by an independent body (one that was not party to the multiplepoinding) as the start point of a new civil action, because what had taken place to date was a travesty.

Anyway my story was never going to be in the news, because despite the fact that a stenographer typed busily the entire two hours it took me to make my submission, and a similar period of time for the submissions of Stephen House, the Pursuer, I was later informed there was no official record of the hearing! Not one word.

The stenographer? She was typing other, general work, invoices etc. for the courts I was told! ☠

Nothing left to do but complain and move on.

Following my hearing of 20th March, 2015, I complained to The Director of Scottish Court Service about retired judge Lord Philip’s conduct at the hearing and Lord Brailsford’s arrogant and dismissive conduct at an earlier stage (this had come to light through notes from him and his clerk Kathryn Keir), as well as the court process for a party litigant. According to the Rules of the Court of Session I still had to contest my Claim even though I had no confidence in it because of how the date of the wreath had been arrived at. In my complaint I stated that I wanted to abandon my Claim as my experiences before Lord Philip were akin to something one might expect in one of Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwean courts.

Perhaps that was the wrong analogy, because the very description of the item upon which the multiplepoinding was predicated was determined in Turkey by Turkish Government agencies, without any input from Scots experts.

I should have written that I wouldn’t have been surprised if a portrait of Kemal Ataturk and a Crescent and Star flag had been on display in the Court of Session on 20th March 2015.

With no confidence in the date of the gold wreath being anything other than a date attributed to suit the agenda of the Turkish Government I put all notions of Elgin’s gold wreath behind me.

My lesson had been a salutary one. Expenses of over five thousand pounds were awarded to the Chief Constable who had first threatened me and told me that the wreath was Turkish, then told the court he had no opinion as to where it came from, before listing his expenses under the heading “Turkish Crown”. So no preconceived notion of country of origin from him then!

When my own expenses such as costs for the court hearing etc. were added, the total cost to me was about seven thousand pounds.

The only official written matter to come out of the court on 20th March 2015 was a 60 word interlocutor signed by Lord Philip, the text of which had cost me over £100.00 a word.

Never let anyone tell you that Scots Courts come cheap.

Even J. K. Rowling can’t command that rate for writing.

P.S. At time of writing the multiplepoinding is still ongoing. I was told after Lord Philip’s ruling on my objection I was no longer a party to the claim. In a recent development the man from whom the wreath was taken has been refused legal aid to defend his claim. To my mind this seems totally unfair, because unlike me – I joined the multiplepoinding of my own free will – he had no choice but to contest the civil action to claim back what was taken from him by the police. Having forced him into court the authorities then deny him the wherewithal to pursue his claim and leave him to contest a game of ‘who has got the deepest pockets’ with the Republic of Turkey. No prizes for guessing the winner!

Back to school to read up on the so called Elgin Marbles I find that Elgin’s reports of his gold myrtle wreath were greatly exaggerated.

In December 2015, some nine months after my fateful, final, court appearance, I set about researching this subject (Elgin’s Grave Robbery) for a blog to coincide with the bi-centenary of the sale of the Parthenon marbles to parliament.

My earlier, 2001-2004 research of the ‘Elgin Marbles affair’, as I have said, was limited, in that it mainly centred on the works of two academics, Professors, Epaminondas Vranopoulos and David Rudenstine, and of course the various editions of Elgin’s Memorandums.

In an attempt to widen my knowledge on matters Elgin I then read the works of A. H. Smith (Lord Elgin & His Collection), Christopher Hitchens (The Elgin Marbles), Dyfri Williams (Reconstructing a Fourth Century Tumulus near the Piraeus), and others.

My earlier impression from Hunt’s letter to Elgin’s mother in law and from Elgin’s Memorandums was that the ‘Aspasia’ gold myrtle wreath had been discovered when Elgin and his wife had visited Athens in 1802. No doubt that was the impression they were meant to create, but it wasn’t so. What the Elgins saw was the opening of that tumulus – nothing more.

From Williams, Smith et al, I learned that in fact the gold wreath from the ‘Aspasia’ tumulus site that Elgin and his wife had seen opened, or commenced in 1802, was not unearthed by Lusieri until 1804, at a time when Elgin, his wife and Hunt were under arrest in Pau, France.

But more surprisingly I learned that what was unearthed was not a wreath at all according to Lusieri, who on discovering it in 1804, wrote to Elgin describing it as: “a branch of myrtle, of gold”

There is more confusion about this gold myrtle artefact, which was supposed to have been taken by Lusieri to Malta on the Hydra which sailed from Piraeus on 22nd April 1811with the last of the Parthenon marbles. Lusieri was accompanied on this voyage by Byron and it is assumed he deposited the wreath at Malta together with the marbles all of which would then be shipped on to England.

Valetta harbour in Malta was at that time the lazarette port where all persons or goods from the Levant were quarantined pending clearance before onward transit to European ports.

However Lusieri returned to Athens in July of 1811 and some time later in September 1811 he wrote to Elgin saying that the inner bronze urn in which it had been found was at Malta, but he had: “the little gold spray of myrtle that was in it here. The person who stole it was so kind as to sell it to me.” [Williams; page 421, says he thinks in this letter Lusieri was mistaken in thinking he had the gold spray of myrtle with him at Athens. I think not]

Regardless of that confusion, when Hunt had been waxing lyrical in his letters and Elgin’s Memorandums about a gold wreath of myrtle etc., he had not even seen the artefact in question, and probably never did see it. Nor had William Richard Hamilton or indeed Elgin seen it when the Memorandums were published, as it only came into Elgin’s hands in 1825, that is some four years after Lusieri’s death, and even then in dubious circumstances.

This is my understanding of how Elgin came to own it: In 1820 Lusieri, was still at Athens even though Elgin had served him with notice in January 1819 that his contract terminated at the end of that year.

This caused Elgin a problem, because Lusieri retained many valuable artefacts at Athens that belonged to him.

So on October 15th 1820, Elgin wrote to his former secretary, William Richard Hamilton, who was Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs at Naples seeking his help, he explained that Lusieri’s was on notice of his contract ending before stating that he was very keen to get his hands on Lusieri’s drawings and paintings and other artefacts: “especially the golden wreath of myrtle, found in the vase, in Aspasia’s Tumulus“.

Hamilton was later able to help his old friend in this request, and after Lusieri died in 1821 he had Lusieri’s personal possessions, consisting of two boxes and a tin case which had been in the care of the harbour master at Valetta sent, aboard H.M.S. Cambrian, to his offices at Naples.

In 1822 Hamilton was elevated to the post of Minister and Envoy Plenipotentiary at the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and it would appear that he was in that position at Naples when he confiscated the gold myrtle wreath from Lusieri’s boxes on the basis that it was the property of Lord Elgin. Hamilton reached agreement with Lusieri’s heirs in February 1824 on the remaining contents.

Lusieri would seem to have planned to keep the gold myrtle spray as his own (who could blame him?), and, as he hadn’t been paid for some time, he may have had just cause to retain the gold spray as well as his oil paintings and sketches in lieu of unpaid wages.

Anyway from my research I had a new set of parameters to guide me in my search for the whereabouts of the loot from the ‘Aspasia’ tumulus; it wasn’t Elgin’s “gold myrtle wreath”, which I had previously searched for, but Lusieri’s “gold mytle spray” that I now looked to find.

A monkey reveals the whereabouts of the gold myrtle wreath or branch, or little spray, or is it a sprig – with a little help from Alice!

Lusieri’s gold myrtle branch or little spray that he found inside a bronze urn in the ‘Aspasia’ tumulus was revealed to me as having been on display in Edinburgh between 30th June and 28th October 2012, at the National Gallery of Scotland.

I found it via a Google Search, which led me to a monkey!

Or to be more precise, Vera’s Monkey.

Oh and it wasn’t the spray Lusieri described, Monkey was now calling it…. a ‘sprig’.

Vera’s Monkey blogspot disclosed the ‘Aspasia’ gold myrtle ‘sprig’ was part of an exhibition of Lusieri’s works entitled: “Expanding Horizons: Giovanni Battista Lusieri and the Panoramic Landscape.”

Vera’s Monkey blog also revealed that The British Museum now owned the gold myrtle sprig, which they had loaned to the National Gallery, together with the bronze urn it had once been buried in, to compliment Lusieri’s painting entitled: “A Greek Double Urn”.

The Monkey in question had attended the event with his/her/its friend Alice who was a ‘Friend of the National Gallery’ and placed the following photograph on his/her/its weblog:

Photograph of the bronze inner urn (dinos) with the gold myrtle sprig on top as displayed in The National Gallery, Edinburgh June-Sept, 2012.

So at a time when the Turkish Government and a Turkish restaurateur were writing to the police with competing claims of ownership of a Turkish gold myrtle wreath; a Greek gold myrtle sprig of identical form, material and manufacture, was being exhibited in the same city.

What Elgin described as his gold myrtle wreath from the ‘Aspasia’ tumulus could be viewed atop a bronze urn by anyone (anyone with a £5 admission fee that is) in the National Gallery, Edinburgh.

At the same time, the gold myrtle wreath, which I would later think might be Elgin’s, and the police believed to be Turkish, was then, and still is now, under lock and key at the Fettes Police HQ Edinburgh, where no one is allowed to see it, unless of course you happened to be from the Turkish government.

Had I known of the Lusieri exhibition and the gold myrtle sprig from the ‘Aspasia’ tumulus there would have been no claim by me in the multiplepoinding and I could have saved myself a lot of time and money.

I need to get out more to cultural events it seems……..or pay more attention to bloggers who do.

Monkey – with a little help from Alice, also points me in the direction of some of Elgin’s graveyard loot.

Having previously searched for a gold myrtle wreath on the British Museum website some years ago without success, I returned to that website buoyed by a certainty of purpose derived from the Monkey’s blog and searched their ‘Collection online’ where I found not a sprig, but a “gold myrtle spray”. It was also shown with the bronze urn (dinos) that it decorated in the same photograph Monkey had used.

The British Museum catalogue described the gold myrtle spray thus: ornament, Classical Greek; 400BC-350BC; Eleusis; Piraeus. The British Museum also quoted the A. H. Smith book reference as well as the fact that it had been loaned out for the Lusieri exhibition in Edinburgh. The spray was stated as having been bought in 1960, with a contribution from The Art Fund, from the previous owner/ex-collection: Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin.

I then searched the ‘Collection online’ section, using the terms ‘Thomas Bruce’ which revealed: “Your search for Thomas Bruce returned 1,353 results.”

As well as the bronze urn and gold myrtle spray the Thomas Bruce search revealed a host of other loot that Elgin had taken from Greece, but which had not been bought in the, Visconti-catalogued lot, by the Westminster parliament in 1816.

There were many precious rings, earrings, necklaces, brooches, vases and hundreds of coins labelled as ex-Thomas Bruce Collection. The date of purchase by the British Museum range from 1816 up to the present time.

I ordered some images from the British Museum’s free image service and they are featured on this blog.

I am sure that even this hoard doesn’t account for a fraction of the full amount looted by Elgin from hundreds (thousands?) of graves in Greece. Little wonder then that two days after Pisani obtained his firman in 1801 allowing Elgin’s party in Athens to dig, Elgin wrote to Lusieri who was in charge of the Athens team proclaiming triumphantly: “you now have the permission to dig.”

A grave robber’s charter had been handed to Elgin and he made the most of it.

The extent of Elgin’s looting is hard to grasp, but he told the Chairman of the Committee of Parliament Henry Bankes Esq. in 1816 that he: “employed three or four hundred people a day” at Athens.

When one considers that Edward Dodwell, who like Elgin plundered graves in Greece during the same period, wrote that his ten man team, with sledge hammers and levers could crack open 30 tombs a day, Elgin’s team of hundreds of men must have done untold damage. For every one of the hundreds of whole urns that Elgin sold to parliament there must have been ten that were shattered by the ravages of his tomb robbers who were only interested in finding valuables within the vessels.

I am firmly of the opinion that the outer marble vase that held the bronze container at the ‘Aspasia’ site was not, as Lusieri says, broken by: “the enormous weight of the tomb” rather it must be the case that it was broken by the sledgehammers used by his own team in the manner Dodwell describes to break the tomb’s flat covering stone .

If it were, as Lusieri colourfully claims, the enormous weight of “sand brought from different streams which cross the plains of Athens.” why did this same pressure not crush the very fine vase of alabaster which lay “On the outside and beside the [marble] vase”?

No, Lusieri was a fine artist, but more infamously was Elgin’s chief grave robber and his painting above of the double urn is a record of his own vandalism.

Here are some of the pieces that Elgin’s army of grave robbers looted from Athens which now reside in the British Museum. It is a source of bitterness to me that many of the items held by that institution have been bought from the ex-Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin’s collection, with the help of public money.

Clockwise from top: Aspasia gold myrtle sprig, Necklace, Rings, brooches, ‘Elgin’ Dipylon vase. Photos courtesy of British Museum.

200 years after Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, sold his main collection to parliament, who bought them on behalf of the British people, the same British people have, on a regular and ongoing basis subsidised the buying of more loot from Elgin’s Greek adventure. This makes us all guilty by association with his wicked, imperialistic, crimes.

Appendix

Did Giovanni Battista Lusieri have the last laugh on Elgin.

Most of my misunderstanding of the exact nature of Elgin’s gold myrtle wreath came from believing what I read in the letter written by Philip Hunt from Pau, France on 20th February 1805 and the various Memorandums written, in the main by the same man and embellished by Elgin and Hamilton.

I should have known better than to believe these proven liars.

Hunt wrote of a gold myrtle wreath in his letter to Elgin’s mother in law adding “having besides leaves, both buds and flowers” in the Memorandums.

Hunt had never seen the item about which he wrote, and perhaps he never did see it, as it was not discovered by Lusieri until March 6th 1804 and as explained above, was not confiscated by Hamilton on Elgin’s orders until after Lusieri died in 1821.

When Lusieri had discovered it on March 6th 1804 he wrote Elgin shortly afterwards on 18th May, 1804, describing the contents of a bronze vase thus: “in the interior of this latter, there were some burnt bones, upon them a branch of myrtle, of gold, with flowers and buds.”

So whatever impressions Hunt had when writing Elgin’s Memorandum, were gleaned from Lusieri’s letter of 18th May 1804, to Elgin; or from reports from travellers who had been at Athens and seen Lusieri’s plunder.

Now by anyone’s interpretation what is pictured below (and other views of it on the British Museum’s website), could not be described as a wreath, or a branch, it is simply a spray (Lusieri’s & BM’s description) or a sprig (Monkey blog’s & Williams’s description).

Nor does it have any buds [plural].

Courtesy of the British Museum.

I have difficulty in believing that for over 16 years Elgin believed that the ‘Aspasia’ tomb had provided him with a gold myrtle wreath when in fact it was a small spray he had acquired.

Considering that Elgin was the most informed figure about the arts in that area of the world, as well as his position in the Levant Company and in diplomatic circles, he would have known from his fellow countrymen and women – who flocked to Greece as collectors at this time – exactly what Lusieri had acquired.

Yet from 18th May 1804, the date Lusieri wrote to tell Elgin of his find, up to the 15th October 1820, when Elgin wrote to Hamilton from Munich he still referred to his gold or golden wreath of myrtle.

The Edinburgh gold myrtle wreath the police hold at present has 50 leaves and couldn’t be mistaken for the British Museum’s gold myrtle spray which has 6 leaves.

I find this all very puzzling. I wouldn’t see a bride and groom at a wedding and mistake her floral wreath headdress for his buttonhole flower, but that is what Hunt and Elgin did…unless.

Unless what Hamilton seized in Naples from Lusieri’s personal effects sent from Malta was not the item taken from the so-called ‘Aspasia’ tumulus.

It is a matter of record that Lusieri was latterly short of money due to the failures of his cash-strapped employer Elgin.

Could Lusieri have substituted the gold myrtle branch with buds and flowers he recovered from the ‘Aspasia’ tumulus with a smaller gold myrtle sprig without buds from one of the many other tombs he looted?

Or did Lusieri shorten the branch he recovered by cutting it to leave a smaller burial artefact without the buds that he himself had described?

Dyfri Williams in his lengthy examination of the Aspasia Tumulus comments on the unusual fact that this nine-centimetre long gold myrtle sprig, of six leaves and two flowers, had a central bronze reinforcing rod normally associated with wreaths.

Williams suggests “it seems most likely that it did once actually form part of such a wreath.”

In my long experience in engineering and in particular large and small pipework fabrication I would agree with Williams on this point. A wreath of hollow tubular construction would need an internal stiffening rod, or something to stop its walls creasing or collapsing when it was bent to form the, almost complete circle, of a wreath.

Tubes are often packed with sand, a mandrel, or an internal bending spring of slightly smaller diameter than the tube during bending so as to avoid the pipe distorting to oval and maintain the diameter. These temporary aids are removed after bending.

But an annealed bronze rod would also be ideal for this task and it would be much cheaper than making the wreath’s main stem from solid gold bar.

As no internal stiffening is required on a short straight sprig, the presence of one supports Williams’s theory that Elgin’s sprig was cut from a wreath.

In early nineteenth century Athens, a sprig, cut from a wreath or longer branch (that had been a wreath straightened to fit into a burial urn?) would have solved Lusieri’s wages problems, but left him with an anomaly as to the description of what remained. In the event this was an anomaly he didn’t have to clarify.

There is of course another possibility, and that is that a full-length branch was brought home to Broomhall and one of Elgin’s young descendants hacked off a chunk of the branch/wreath by accident while playing soldiers and used the buds as marbles, leaving only the stump of their ancestor’s find to be sold to the British Museum in 1960.

Please excuse my little joke here, I thought the viewer must be getting bored by now.

Seriously though, there is a very important point in my joke in that we don’t know what Greek treasures Broomhall houses, and often we only find out about them long after they are sold. This is a source of concern worldwide as evidenced by this Greek language magazine article from Parapolitika.

The gold myrtle wreath/branch/spray/sprig is but one of the many anomalies in the accounts of Elgin’s looting, but when tales are told by liars and when thieves fall out what does one expect.

Elgin’s looting was all about conservation of the arts for British aficionados…I think not.

Perhaps the most damning aspects of the ‘Aspasia’ tumulus loot are revealed by Dyfri Williams in his article: “Reconstructing a Fourth-Century Tumulus near the Piraeus”.

Williams reveals that the unique ornate alabaster vase or alabastron – a drawing of it by Lusieri is at Broomhall – described by Lusieri as being found beside the double urns was somehow lost.

Not only that, the bronze lid to the inner bronze urn recovered by Lusieri and depicted in his ‘Double Urn’ painting was also lost.

As if that were not bad enough, the British Museum, which held the double urns for over a hundred years in the belief that they may be from the burial tumulus of Aspasia (470-400 BC) only found, when giving the bronze urn a light cleaning after the First World War, that it was clearly marked in Greek thus: “I am one of the prizes of the games for Agrive Hera”

Williams tells us these athletic games in honour of Hera were held between 460 and 430 BC so unless Aspasia had been a running/javelin-throwing champion, a sort of Ancient Greek, Tessa Sanderson, that we didn’t know about, who was buried with her sports trophy in a tumulus on the road from Port Piraeus to the Salaminian ferry and Eleusis, the tomb was not that of Aspasia.

So in summary: Our British champions of conservation in the persons of Elgin’s team and the experts at the British Museum: lost the lid of the bronze urn; lost the elaborate alabaster vessel found with it (described by Hunt in the Memorandums as a lachrymatory), which was over 48 centimetres high and almost 10 centimetres in diameter, and then, for over a hundred years didn’t brush off the dirt to see the inscription on rim of the bronze urn [dinos].

And that is before we even look at Elgin’s precious cargoes lost on sunken ships.

And we say the Greeks can’t look after their own artefacts!

P.S. TIME SOME OF THE GREEK DIASPORA STARTED TAKING THE BM TO COURT WITH REGARD TO RELICS LIKE THE ‘ASPASIA’ GOLD WREATH NOT COVERED BY BM ACT!

UPDATE 10/06/2021:Aberdeen Uni have decided to return looted Benin Bronze as it was “was acquired in such reprehensible circumstances” Bravo the Dons, following Glasgow’s Lakota Ghost Dance Shirt repatriation.☠

UPDATE: 03 Aug. 21

A recent article in the Glasgow Herald by Neil Mackay entitled: “Decolonisation, Empire and repatriating looted art – life inside Scotland’s National Museum amid culture wars” gives the views of the National Museum of Scotland’s Director, Professor Christopher Breward, who states with regard to looted art: ““We’ve always been able to consider requests for the transfer of objects back to other countries where there’s a clear case to be made,”

Progress! ☠