I confess that for some time I had a soft-spot for the lassie from East Lothian.

I confess that for some time I had a soft-spot for the lassie from East Lothian.

I have long had a certain amount of sympathy for Mary Nisbet (18 April 1778 – 9 July 1855), unlike my feelings for her husband, father and friend Philip Hunt.

Mary married an impoverished land-owning aristocrat on the opposite, north, side of the River Forth, from where she lived. Though she may have been in love, there’s little doubt that she, and her wealthy parents, were also pleased that she would join the nobility on her own account as the Countess of Elgin, or Lady Mary Bruce, when she married Thomas, the 7th Earl of Elgin, an aristocrat with a bright future.

In turn, the cash-strapped Elgin would have been pleased with the marriage to Mary. He had been advised to get married if he wanted to further his career in the diplomatic service. He also needed to get his hands on Mary’s wealthy landowning father’s money, to furnish his expensive tastes (especially as he was rebuilding Broomhall from scratch) and no doubt he eyed a share of his wife’s inheritance when her father died.

Elgin had this possible future Nisbet inheritance written into an antenumptual agreement and he also managed to get her father to pay a dowry of £10,000 as a “marriage portion“, which no doubt eased his financial troubles. LINK

The inheritance Elgin eyed would have been a very substantial one. Mary was the only child of William Hamilton Nisbet who had inherited large properties and much land in East Lothian from his parents. William’s wife Mary (nee Manners), was the grand-daughter of the 2nd Duke of Rutland and she was also heiress to large estates in Lincolnshire. All of which would one day revert to Mary.

The fact that the Nisbets had not been enobled was due to that family’s historical support for the Jacobean cause.

The marriage solved problems for both families and created a future powerful dynasty spanning both sides of the River Forth.

Mary Nisbet becomes the Countess of Elgin, after a hitch!

The Nisbet family website reveals that there was some drama at Mary’s wedding to Elgin on 11th of March 1799, and because Mary was upset Bishop Sandford, who conducted the rites, temporarily stopped the proceedings. LINK

One wonders what caused this hitch? Did someone raise an objection when the Bishop asked if anyone knew of any impediment etc.? Did Mary find out that her father had given Elgin £10,000 to marry his daughter? Or did Mary have second thoughts about marrying a man 12 years her senior (she was 20, he, 32), or to one who she suspected/knew had syphilis?

The possibility, more of a probability, that Elgin had already contacted the syphilis that would later blight his life is not a moral judgement on him (though I have plenty to say about his lack of morals in other matters) as he had been a bon viveur on the London scene for some years when he lived there, and it would have been more unusual if he hadn’t contacted a sexually transmitted disease given the abundance of “The Syphilitic Whores of Georgian London” LINK

There was a 9 year period before Elgin married when he was ambassador in Brussels and Berlin, travelling extensively on the continent, where again syphilis was rife and it was known that he was a bit of a rake and had been involved in several scandals involving married women.

Leaving aside speculation as to the reason for the delay, we do know that the marriage ceremony was completed and within four months Mary was pregnant. If Mary’s marriage to Elgin had been a long and happy one he would, one day, have became a very wealthy man.

It wasn’t, he didn’t, and the rest is history, but it’s a history with many unanswered questions, so that to this day it is still the subject of debate and revision.

For example, the impression I had of Mary was that of a spoiled, only child, of a rich father who was spirited if not flighty, but was basically decent. The very opposite of her ambitious, greedy and serious husband, but read on and see how I was forced to review that notion.

Most of what we know of Mary Nisbet’s life with Elgin comes from a book written in 1926.

Of course my impression of Mary was gleaned from books written about her after her death, most notably “The Letters of Mary Nisbet of Dirleton (1926)”. This book that contained many of her letters written during the period she was married to Elgin, or Elky/Elchy Bay or simply E as she sometimes called him in her writings. The book was edited by her great-grandson, John Patrick Nisbet Hamilton Grant.

Of course my impression of Mary was gleaned from books written about her after her death, most notably “The Letters of Mary Nisbet of Dirleton (1926)”. This book that contained many of her letters written during the period she was married to Elgin, or Elky/Elchy Bay or simply E as she sometimes called him in her writings. The book was edited by her great-grandson, John Patrick Nisbet Hamilton Grant.

There is little doubt that Mary was spirited as evidenced by some of her antics. She spent much of her youth in London where her father was a member of parliament and moved in the very top levels of society. Once married she didn’t flinch at the challenge of travelling with her husband to Constantinople, a place that few western women had visited.

When in Constantinople Mary dressed as a man so that she could be present when her husband was presented to the Sultan in the strictly male-only confines of the Topkapi palace. Later Mary sneaked into the Sultan’s harem (Seraglio) to gossip with his concubines and later still wanted to send her children home to Scotland by balloon so that she could take up residence in Cairo as ambassadress. Mary also relished the action of a sea battle, when the ship she was travelling in fought and sank a pirate ship. All this and much more is testimony to the fact that Mary was a woman of character and no shrinking violet.

Similarly there is little doubt that at one time Mary was besotted with her new husband, but also little doubt that she became increasingly burdened by his ill health and how this impacted on her and her children.

By as early as 1801 Elgin’s health was in a poor state. He was subjected to severe headaches and his nose was wasting away on his face to such an extent that his doctor was reduced to treating it by bleeding with leeches and applying mercury to it.

With a leather patch covering where his nose used to be, Mary’s ‘Eggy’ could hardly then have been the dashing, romantic figure, who had caught her eye a few years earlier.

The renovation project for Broomhall & Biel runs away with the money.

Added to Elgin’s health issues, after a year or so in Constantinople, the family faced financial strains on their limited budget. Elgin was on a fixed salary with expenses said to barely cover the embassy costs, and Mary’s father restricted her allowance to the interest on a £10,000 bond. These factors caused them to dispense with their chamber orchestra and many of the “Hottentot servants” that they began their rather lavish embassy with.

Elgin’s private enterprise in collecting architecture and other valuable relics was a major drain on money, albeit that after a while it was financed by his father in law following his visit to Athens, at which time he became caught up in Elgin’s looting spree.

But William Hamilton Nisbet expected returns on this investment, and though the joint venture to furnish Broomhall (the Elgin’s home) and Biel (Hamilton Nisbet’s) started off brightly with HMS Patheon quickly returning booty in the form of the Sigean and other marble treasures to England, there was then a delay of almost 2 years before further substantive returns. The next shipment came in the form of Constantine’s sarcophagus lid and other porphyry items. LINK

William Hamilton Nisbet and his wife had visited Athens to see Elgin’s operations there under the supervision of Lusieri and while there they had collected a valuable marble gymnasiarch’s and were impressed by the industry of Elgin’s asset strippers, but they would have been conscious of the costs of keeping a staff of hundreds that Elgin employed. They would have also been acutely aware that the big prize, the Parthenon frieze was the one that might make it all worthwhile.

So when, on 17 September 1802, the cargo ship, the Mentor, that Elgin had built specifically to take valuables home sank off Cape Avlemonas, with most of the Parthenon frieze and the Hamilton Nisbet’s gymnasiarch’s chair on board, this must have placed a strain on Elgin’s relationship with his main backer, William Hamilton Nisbet. As well as on his marriage to that man’s daughter.

So when, on 17 September 1802, the cargo ship, the Mentor, that Elgin had built specifically to take valuables home sank off Cape Avlemonas, with most of the Parthenon frieze and the Hamilton Nisbet’s gymnasiarch’s chair on board, this must have placed a strain on Elgin’s relationship with his main backer, William Hamilton Nisbet. As well as on his marriage to that man’s daughter.

To Mary, the arrogant ambassador who had seemed such a good prospect when she had married him, had, in the space of a few years, become an unhealthy, hapless and expensive liability.

At this point did Elgin’s marriage founder like the Mentor? The Mentor’s cargo was recovered by divers, but Elgin’s marriage eventually could not be salvaged.

The Elgins are homeward bound, but for Mary’s hapless husband there’s more trouble in store.

In January 1803, when Elgin’s embassy to the Porte ended, the family (now of five) left Constantinople for home on HMS Diana (La Diane), just over three years after arriving there in November 1799.

In January 1803, when Elgin’s embassy to the Porte ended, the family (now of five) left Constantinople for home on HMS Diana (La Diane), just over three years after arriving there in November 1799.

They sailed for home via Athens (passing the site of the sunken Mentor where divers had begun to salvage the cargo) to Malta, where it was decided they would part company with their three children who would go home on board the HMS Diana.

Print above shows the 38 gun frigate, H.M.S. Diana capturing the french brig L’euphrosyne, in the English Channel on June 1, 1803. Painting by Tom Freeman

For a young mother to leave her three children aboard a ship, even a disciplined Royal Navy vessel with a doctor on board, takes some understand and it appears that this decision was not to Mary’s liking.

However Elgin and Mary after spending a few weeks in Malta with friends then went by boat to Naples then on to Rome where they spent Holy Week.

From Rome the Elgins decided to journey home overland and while travelling through France Elgin was arrested. This was because he was an Englishman of military rank who, if he returned to England, may have taken up arms against France. All that was initially required was that he surrender his passport and give his word that he would not leave the country.

Again, this incident highlights that – like so much else he did – Elgin’s judgement was poor. Initially his party (which had been joined by Robert Ferguson a fellow Fife land owner) stayed with him in Paris and they moved on to Barages/Pau with him, when he went to the spas there to ‘take the cure’ for his syphilis-related ailments.

At this time Mary was in the early stages of pregnancy with her fourth child and this move added more pressure to her, as the lively Mary was not suited to the drab existence associated with Elgin’s daily health treatments in spas in rural France. In November of 1803 Mary left Elgin in Pau and moved to Paris accompanied by Robert Ferguson ostensibly to get her passport and return to England to have her fourth child.

The remainder of Mary’s married life to Elgin was troubled. She gave birth to two more children to Elgin (one, who Elgin thought was not his child died an infant in Paris), and then she fell madly in love with Elgin’s friend Robert Ferguson.

Caught up in this emotional triangle Mary refused to have sex with her husband when he returned to England. Elgin successfully petitioned parliament for divorce and then sued Ferguson in London for £20,000 for spoiling his wife. Following this he sued Mary in Edinburgh to have her wealth given over to their children, whom he had custody of.

Elgin won £10,000 in the London action, but he failed in the Edinburgh courts to have Mary declared unfit to manage her affairs (despite accusing Mary of having been caught with Ferguson on a couch with “her petticoats up” while married to him). Mary emerged from this, the major scandal of the day, and married Robert Ferguson living happily with him on his Raith Estate some 15 miles east of Broomhall.

It is impossible to judge who was to blame for the Elgin’s marriage breakdown, but I had sympathy for Mary because the man who had promised so much to her, had, in the end, delivered little other than their children, one of whom predeceased his mother because he was diseased like his father, and like his father died with a nose eaten away by mercury.

Though she had faults, overall I liked history’s tale of Mary Nisbet. She was a rebel who flouted convention and I liked her for that.

Recently my favourable opinion of Mary Nisbet has been stood on its head!

The reason for my volte-face came in a letter Mary wrote to her father on 14th/15th of March 1801. LINK

When I first read the letter in the 1926 book I had thought that it gave testimony to Mary’s loyalty and enthusiasm in helping her father collect artefacts, in this instance porphyry columns, for her home at Broomhall and his home at Biel.

The letter, after introductory pleasantries stated: “But now my Dearest Father prepare to hear with extasy what I am going to tell you! Captain Briggs Commander of the Salamine Brig has at this moment on board………………”

The letter went on to detail the porphyry columns that she, as a dutiful daughter, had managed to get loaded on the ship for transport home, and ended with a triumphant note in expectation of approval: “What say you to this Dearest Dad”

While not approving of Elgin’s or Hamilton Nisbet’s collecting/looting of architecture and artworks, I could forgive Mary Nisbet for throwing herself enthusiastically into helping her husband/father. She was after all well aware of the large outlay of money they had made and wanted to help balance the books.

That was until I saw the full text of this letter.

Mary Nisbet’s letter reveals an ugly side to her nature, mocking a sultan who had lavished her with kindness.

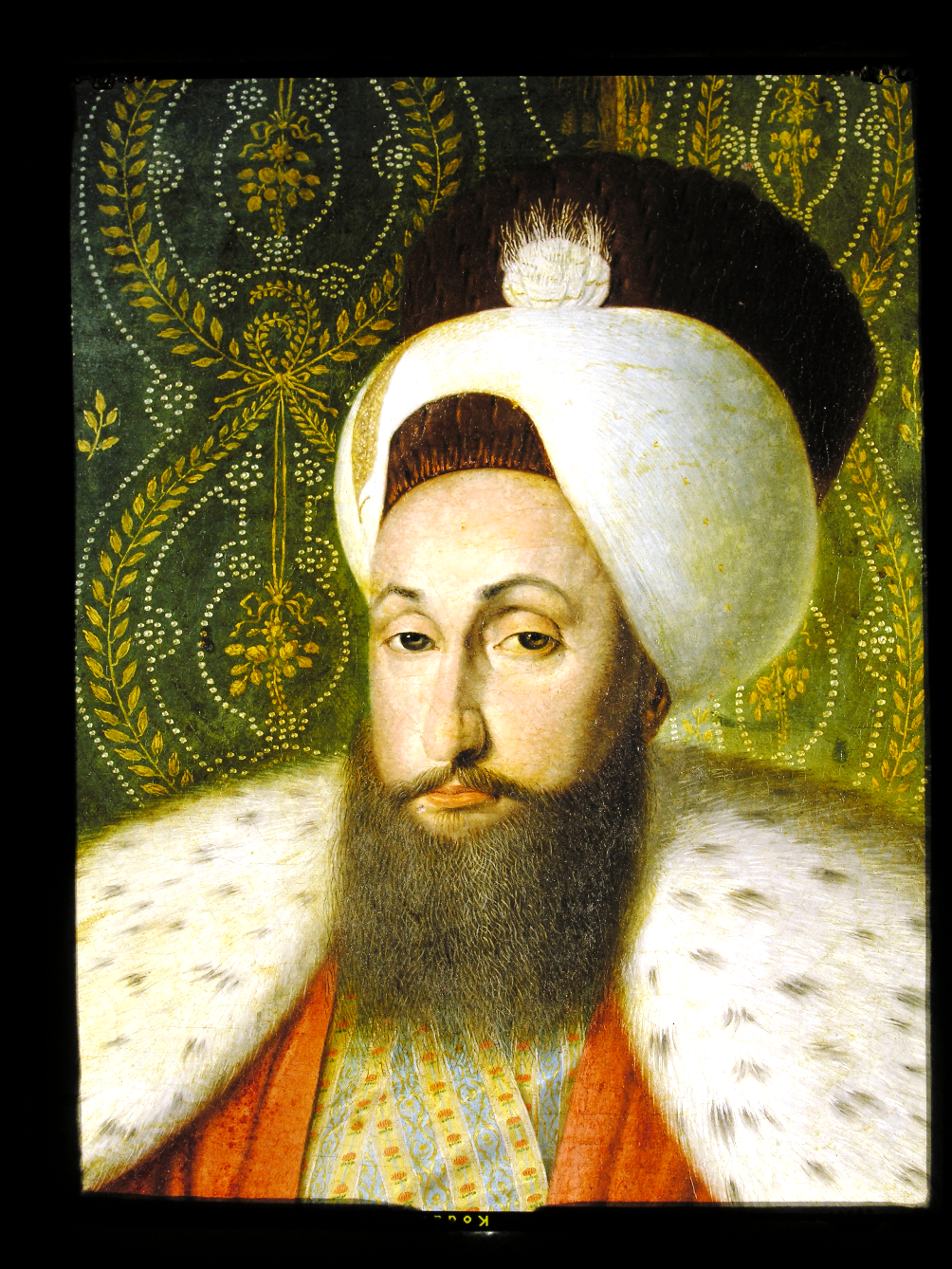

The actual text of the letter shows that Mary asks her father (who had now returned home) to hear with extasy, a report of how her husband Elgin had humiliated Sultan Selim III by asking for certain pieces of porphyry, which were in the mosque of the Seraglio. Then when this request was deemed impossible and an alternative artefact in porphyry was brought to Elgin as a gift from the Sultan, he threw it out of an open window without deigning to look at it, exclaiming he “would have all or none”.

This caused Sultan Selim III to offer an alternative gift from the Seraglio the next day and eventually to give in to Elgin’s demands.

Mary having asked her father to hear ‘with extasy’ this hubristic act on the part of her husband then ended by condoning, even gloating at his bullying behaviour by mocking their host:

“Gibbon would have said Elgin had coaxed or bullied Old Selim out of these bits of Red Stone.”

In my opinion Mary Nisbet by glorying in her husband’s treatment of a man who had showered them with kindness and lavish gifts of jewels and money was beneath contempt.

The transcript of the letter supplied by the British Museum is here: LINK

The photos of the letter, courtesy of the British Museum, from which the transcript was taken is here: LINK

Sultan Selim III, a detail from a portrait in the Topkapi palace museum. Selimi was a soldier first, but also a gifted musician, educationalist and reformer who opened up the Ottoman Empire to the west.

History will have to be re-written for Mary Nisbet.

What does this letter tell us? Well to me it says that we cannot rely on the edited letters of Mary Nisbet from the 1926 book for a true picture of what happened in her time in the Middle East.

Did authors or academics rely – as I did – on the flawed 1926 book that distorted the true nature of “The Letters of Mary Nisbet”?

Susan Nagel author of “Mistress of the Elgin Marbles” 2004, certainly did.

She used the 1926 edited book version and quoted the sanitised version of Mary Nisbet’s porphyry letter and not the actual letter. This is odd given that in the Preface to her book she thanked Justin Hope Brooke (a direct descendant of Elgin and Mary Nisbet) who, in 2002, sold the letters to the British Museum. Perhaps he forgot what was written in the letters of his ancestor?

Or is it more likely that Julian Hope Brooke (formerly of Biel, the Hamilton Nisbet family home inherited by his father Vice-Admiral Basil Barrington Brooke) kept Nagel in the dark and fed her a sanitized 1926 version of the life of Mary Nisbet, just as Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin did with A. H. Smith.

Brooke, having sold the real story of Mary Nisbet and Elgin – the 170 letters & documents – to the British Museum knew that the Nisbet family’s dirty little secrets would remain safe and unpublished in the vaults there. Just as Victor Bruce knew the selective, anodyne ingredients he gave Smith would not make a potent brew.

Of course there will be some facts in the 1926 book that are accurate, but as seen in the June 1801 letter there have been pertinent facts removed from the original letter to spare the character of Mary Nisbet and Elgin which change the very nature of this letter.

In the one letter of the 170 that I have seen there is no judicious editing, but instead there is a deliberate distortion aimed at removing Mary and Elgin’s atrocious behaviour from the public eye. Lieutenant Colonel John Patrick Nisbet Hamilton Grant (a descendant of Lucy Bruce, Elgin & Mary’s youngest daughter, who inherited Biel), made a gallant attempt to reform the reputation of his ancestor by a ‘cut & paste’ of what she actually wrote, but in this letter at least his efforts are in vain. He has been found out.

William St Clair relied on the 1926 publication: “The Letters of Mary Nisbet” in dozens of instances. Here is part of his page notes to show the extent of his reliance on the book. LINK

This reliance on flawed authorities surely means that his book “Lord Elgin & The Marbles”, published in various editions since 1967 will now have to be considered as flawed, or part fiction, relying as it does so much on a vanity publication, a puff-piece on Mary Nisbet?

If I were in St Clair’s shoes I think that I would be consulting lawyers to sue the British Museum for damages to my reputation.

Keep it in the family is the way to protect their ancestor’s reputation.

A. H. Smith used what he described as ”many extracts from her lively letters” [Mary’s] and while some come from the letters Mary Nisbet wrote to Elgin’s mother the Dowager Countess and would be from the Elgin archives, some would not.

Smith’s publication predates the 1926 book, but would John Partick Nisbet Hamilton Grant who inherited the estates of Biel, Archerfield and Dirleton in East Lothian be just as circumspect before he wrote his book with what he shared with Smith, as he was afterwards with the public?

Or even if Hamilton Grant gave Smith full access to the Letters of Mary Nisbet ‘warts and all’ would Smith (an Elgin/Nisbet relative by marriage) have published the detail such as that above which showed Elgin and Mary in the worst possible light? I think not.

Where do we go from here? The British Museum crypt?

The British Museum has a charter obligation to inform the arts in this country. They are failing in that obligation by not publishing letters that play a pivotal part in explaining the events that led to parliament buying (on behalf of the people) the so called Elgin Marbles in 1816.

Of the 170 letters and manuscripts bought by the British Museum from Justin Hope Brooke in 2002 there isn’t even a catalogue or index of what was bought.

I had some difficulty in obtaining one letter from the British Museum and having asked for the availability of another (which I am again prepared to pay for) it seems as if they are not talking to me in any meaningful way, instead engaging in obfuscation by asking me to quote the text of the letters I require photographs of. This is simply not good enough.

The British Museum should not be able to buy-up historically important letters so that they can keep them from those who wish to research the historical events they relate to.

The British Museum must publish all of the Mary Nisbet letters and allow us to make a judgement on what she wrote, as opposed to what injudicious editing (Spin) portrays her as writing.